This review appeared in the Vol. 19 No. 1 / Spring-Summer 2012 issue of West 86th. A response to this review from exhibition curator and catalogue editor Kevin W. Tucker can be read here.

Exhibition:

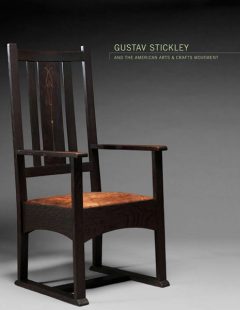

Gustav Stickley and the American Arts and Crafts Movement

Newark Museum, Newark, NJ

September 15, 2010–January 2, 2011

Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, TX

February 13–May 8, 2011

San Diego Museum, San Diego, CA

June 18–September 11, 2011

Catalogue:

Gustav Stickley and the American Arts and Crafts Movement

Edited by Kevin Tucker

Dallas, TX: Dallas Museum of Art / New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010.

272 pp.; 170 color ills.

Cloth $60.00

ISBN: 978-0-300-11802-5

Gustav Stickley (1858–1942) is widely regarded as the central figure in the American arts and crafts movement, which lasted from the mid-1890s until the end of the First World War.1 Considering Stickley’s importance, it is odd that no monographic exhibition of his work should appear until the fall of 2010 with Gustav Stickley and the American Arts and Crafts Movement, organized by the Dallas Museum of Art under the direction of Kevin Tucker. Tucker edited a catalogue to accompany this well-designed show, with contributions from David Cathers, Joseph Cunningham, Beverly Brandt, Tommy McPherson, and Beth Ann McPherson. Since there is a considerable difference in content and quality between the exhibition and the catalogue, this review will consider each as a separate topic. And, as the show was organized by the Dallas Museum of Art, I will consistently refer to Dallas as its home venue.

The Exhibition

Because his endeavors ranged so widely–manufacturing, trolley transit, architecture, object design, lifestyle advice, and publishing, to name a few–Stickley’s life and career present challenges for any scholar. His enduring Craftsman furniture remains his greatest legacy and for decades has commanded both rapt attention and high prices in the decorative-arts marketplace. First brought to light in Robert Judson Clark’s exhibition at the Princeton University Art Museum in 1972, Stickley’s creative work has subsequently been attributed not only to “the Craftsman” himself but also to several talented associates, such as Harvey Ellis, Louise Shrimpton, and M. Lamont Warner, presenting researchers with a trail of often confusing evidence on which to base assessments of significance.2 Of particular importance are the exquisite designs of Ellis, whose brief employment with Stickley transformed the entire Craftsman style, lifting it beyond the experiments of the 1901 United Crafts catalogues.3 For the first time in a major exhibition, the Dallas exhibition made it possible to appreciate the contributions of various designers within the Craftsman studios in a comparative setting, with analysis from some distinguished interpreters of the work. Far from diminishing Stickley’s importance as an artist and cultural force, the variety enriches our understanding of his particular genius.

There is no dearth of written material on Stickley’s life and work. Three biographies, beginning with Mary Ann Smith’s Gustav Stickley: The Craftsman in 1983, present a fascinating Horatio Alger tale of a Wisconsin farm boy making his way in American business to become a trendsetter in New York City after 1900.4 It is no exaggeration to speak of a Craftsman business empire envisioned and directed by Stickley. At its height it included a nationwide network of dealers and had market reach rivaling that of many a modern-day corporation. Biographers have marveled at Stickley’s energy and productivity, while struggling to explain his abrupt fall after a devastating bankruptcy in 1915.5 His character remains elusive, despite attempts to trace the circumstances of his boyhood and the specific tensions in his German American family of origin.6

No such ambiguity has hampered the study of his furniture, which was extensively catalogued during Stickley’s time and has been studied carefully during our own, aided by a large collection of photographs and business papers in the Joseph Downs Collection at the Winterthur Museum and Library in Delaware.7 Many Craftsman original catalogues are available, and Stephen Gray has reprinted several at Turn of the Century Editions. In addition, the Stickley-Audi Company today produces furniture based on original shop drawings. Previous books and articles have explored manufacturing and design techniques at Stickley’s factory in Eastwood, New York, established in 1901, contrasting forms with those produced by his brothers, such that today many collectors can spot a “Gus” piece from afar based on detailed knowledge of characteristic motifs and finishes. As more became known about the post-1904 pieces, scholarship focused on the sources and design inspiration for Stickley’s earlier arts and crafts designs, some of which are remarkably similar to European examples, including some secession and art nouveau designs.8 Writing on the furniture since the early 1980s, David Cathers has established himself as the leading authority on the development of Stickley’s mature furniture and decorative arts.9

Only recently has Stickley’s architecture received comparable attention, though scholars have consistently cited his profound influence on middle-class home design.10 My own book on Craftsman Farms in 2001 was among the first full-length studies in this area.11 Since Stickley was not a trained architect, he hired a design staff to produce renderings and working drawings for the Craftsman Home Builder’s Club after 1904. Cathers’s research identified a number of these key designers, E. G. W. Dietrich and Samuel Howe among them. Ray Stubblebine published a full-length study of all the house designs in 2006.12 In addition, the fact that Stickley ran a mail-order house enterprise competing with Sears and Aladdin, while also customizing a number of houses for individual clients, has made research more difficult. Interest in Craftsman architecture has increased with the recent trends favoring sustainable design and the simplification of daily life.

While the timing of Tucker’s exhibition initiative was excellent–coinciding as it did with the centennial of Stickley’s completion of Craftsman Farms–the global economic downturn no doubt constrained both the number of objects he could include and the number of venues he could procure for a national tour. Still, what was on view in Newark, where I saw the show, was remarkably rich and evocative of the best “the Craftsman” had to offer during his mature period. Pre-1904 pieces were chosen to illustrate key steps in the development of the “Craftsman style” as it emerged from early experiments in European-inspired forms. Furniture and objects made in the Craftsman Workshops were amply represented, including a few original linen drawings of house plans. Most impressive was the overall quality of the pieces, both in condition and relative significance. Borrowing from both public and private collections, the curators found a satisfying balance that allowed the public to see real masterpieces of furniture and decorative arts in a highly focused exhibition.

Several early items from the “New Furniture” catalogue (c. 1900), such as the Foxglove Table, Chalet Table, and Tom Jones Drink Stand, began the chronological presentation with a splash. The finishes and forms were so eye-catching that it was hard to stop studying one piece and move to the next. The exhibit texts not only created a compelling narrative but also educated the viewer about the development of Craftsman designs from 1900 onward. Benchmark production pieces, such as the Eastwood Chair, an early rocker, trestle tables, side chairs, settles, and several sideboards, provided the armature, while smaller accessory objects and rare nonproduction pieces rounded out the selection. The intention was to show a unified aesthetic ideal, exactly as the Craftsman magazine presented it over a century ago. Perhaps the most stunning set piece in the show was the model dining room from 1903, assembled mainly from pieces that have descended in the Stickley family and beautifully installed by designer Jo Hormuth.13

Hardware was a medium in which Stickley excelled, producing not only bold strap hinges for his solid-wood case pieces but also chandeliers, sconces, and lamps for tables or for attachment to architectural elements. The exhibition included a number of lamps and other examples of fine metalwork. Of particular note are the Electric Lantern, probably designed by Victor Toothaker, and the innovative Newel Post Lamp. Lighting was essential to creating the warm color palette desired in Craftsman interiors, and the show displayed the lamps in settings that approximated their intended environments. The installation drew on chromolithographs from the Craftsman when choosing appropriate colors and light levels.

No less interesting were the textiles, some collected by Dianne Ayres as inspiration for her contemporary work. The fragile linens and vegetable-dyed threads used in these curtains, table linens, and other fabric designs are not often shown sympathetically, given that Stickley wished to emphasize their “sheer, loosely woven” qualities to enhance translucence. The catalogue even cites evidence that Stickley purchased many of the raw materials from a single source, the Donald Brothers of Dundee, Scotland, which placed emphasis on the structure of its fabrics, much in the same manner as Stickley did in his furniture designs (p. 176). This grouping of textiles was first assembled for the case exhibit Mr. Stickley’s Needle-Work, displayed at the February 2010 Grove Park Inn Arts and Crafts Conference in Asheville, North Carolina.

In the end, however, it is the furniture that gets center stage in the exhibition, and this raises a question about the title: Gustav Stickley and the American Arts and Crafts Movement. If this show was focused on furniture and finishes, why did it not get an appropriately specific title? To speculate on a museum’s intentions is perhaps presumptuous, but the likely answer is that the Dallas Museum of Art wanted a more generic title to appeal to a wider audience, as it sought grant assistance from such agencies as the National Endowment for the Humanities. As the museum director states in her foreword to the catalogue, the purpose was “to provide new perspectives on the design, production, and dissemination of [the Stickley] firm’s works, the important contributions of his talented collaborators, and a deeper understanding of the remarkable legacy of his enterprise in transforming the vision of the ideal household of the early twentieth century” (p. 8). While it is laudable to study furniture and interior design as cultural history, covering the myriad subjects required for a review of Gustav Stickley’s enterprises was clearly beyond the scope of the Dallas exhibition. These ambitious aims led to some problems in the exhibition, but it was the catalogue that suffered most from overreaching claims.

The Catalogue

As befits Yale University Press, the accompanying catalogue is beautifully produced, designed, and printed. All of the objects appear in large-scale color photographs, allowing close study of finishes and details. In this respect the book supports the exhibition admirably. When one reads the essays that occupy the first ninety pages, however, questions arise about the range of subjects, the choice of contributors, and the relationship of the essays to the objects displayed in the catalogue.

The subject matter ranges from highly specific in David Cathers’s essay on Stickley from 1898 to 1900 to broadly thematic in Beverly K. Brandt’s study of the Craftsman Home. An essay by Tommy and Beth Ann McPherson–former director and curator, respectively, of the Stickley Museum–gives a general introduction to Craftsman Farms, even though the museum’s holdings are sparsely represented in the show. And though Harvey Ellis is featured in the exhibition, the collaborator who gets a catalogue essay is Irene Sargent, an intellectual and feminist who has been studied in great detail with regard to the Craftsman magazine, which she helped to found.

When it comes to “new perspectives on the design, production, and dissemination” of Craftsman artifacts, the essays offer very little. Indeed, most of what appears is a repetition of earlier work, either by the authors themselves (in the case of Cathers and the McPhersons) or by unacknowledged scholars whom the writers have chosen to ignore or, worse, whose work has been appropriated without footnotes. The footnote question is quite vexing, as it is consistent throughout four of the texts, as if an editor had stipulated that only primary sources be cited. As shown above, the voluminous work done during the past thirty years forms the basis for what we know about Stickley and his enterprises–it is the scaffolding for the entire Dallas exhibition. Some of this work is in the bibliography, but even that fails to account for all the contemporary research published on Stickley and the American arts and crafts movement. With the exception of Cathers, none of the authors chosen to write had published extensively on Stickley, so ignorance of some key material could be expected.

Had the focus been on the development of Stickley’s furniture and other offerings from the Craftsman Workshops, the first two essays–by Cathers and Tucker–would have sufficed as a reasonable gloss on the catalogue entries. Cathers repeats some key material from his monograph, while also unearthing some new material from furniture magazines and industry advertisements, that illuminates the “moment” when mature Stickley designs emerged and when the ideology of “simplicity” began to drive his work. While this essay is excellent, Cathers’s comparative analysis tends to focus on British and European sources, and on the industry in Grand Rapids, Michigan, to the exclusion of experiments in American guilds in places like San Francisco, St. Louis, Chicago, and Boston. More work in this area would enrich our understanding of how Craftsman pieces fit into the web of early twentieth-century design, and Cathers has the knowledge and acuity to pursue these avenues.

Tucker’s interest, in his essay “Art from Industry: The Evolution of Craftsman Furniture,” appears to be in furniture finishing methods, and here too there is fertile ground to be tilled. His detailed analysis of woods and color experiments in Craftsman furniture forms only the second half of his essay, however. In the first half he goes to great pains to establish the relationship between machine production and handicraft in both Stickley furniture and its propaganda–the early brochures and key articles in the Craftsman. Research in the Stickley business papers at the Winterthur convinced him that he had discovered a new angle on old questions, but he failed to consult or cite a number of sources that had already combed both the relevant literature and the records in great detail. Several authors have published books and articles featuring extensive analysis of the dichotomies between machine furniture production and arts and crafts ideology, yet only Cathers’s monograph is cited.14 Indeed, no other citations of secondary sources appear in the Tucker essay, calling into question his familiarity with this material.

Stickley and his colleagues did produce and market “art from industry,” but readers will gain little appreciation for the scope and complexity of their achievement from the Tucker essay. Many scholars have analyzed, and are continuing to study, the relationship between Stickley’s production methods, advertising rhetoric, Craftsman articles, and the international arts and crafts movement. It is disturbing to find an essay on this topic that so blithely ignores such a deep vein of research.15

The same weakness can be found in Brandt’s essay, “The Paradox of the Craftsman Home.” As Stubblebine learned in his twenty-odd-year quest to find every Stickley home design and track its citations in the literature, summarizing the division between written propaganda, drawings, and built houses is a Herculean task.16 I spent an entire chapter of Gustav Stickley’s Craftsman Farms: The Quest for an Arts and Crafts Utopia on the subject.17 Brandt’s brief treatment of the design sources and ideas that informed Stickley’s Craftsman Homes enterprise is largely a repetition of Stickley’s own rhetoric, which is notoriously obtuse, full of contradictions and laced with half-truths. A few references to popular culture and vernacular sources, many of which I cited in great detail, do not explain the synthesis that brought forth the “Craftsman Home,” which is itself a linguistic conundrum. In fairness to Brandt, it is reasonable to ask why she was enlisted to write an essay on this subject when the number of architectural drawings and photographs in the exhibition is small, too small to convey any understanding of Stickley’s architectural ideas.

An even larger subject, on which much has been written by feminist and material culture scholars, is that of reform in domestic culture during the early twentieth century. The home as a cultural construct, the family as a social unit, and the woman’s role in the domestic environment are critical subjects in early twentieth-century social science research. Stickley’s own home environments, both as constructed and as presented in his writings, are fascinating examples of the desire for a new style of living. Cheryl Robertson, Arlette Klaric, Dolores Hayden, and a host of others have explored this broad subject, offering valuable insights into Stickley’s contributions.18 The McPhersons, whose expertise is in object design, ceramics, materials conservation, and aesthetic theory, are marginally familiar with this research and know Craftsman Farms in great detail. They have published on the restoration of the Log House there already, and some of this work appears in their essay for this catalogue.19 They are wrong to aver that “only rarely” have scholars considered the role that furniture plays in the Craftsman interior or the symbolic, cultural, and functional meaning behind Stickley’s interior decor during the early twentieth century.20

While their essay goes into great detail about the particular interior features of Stickley’s homes in Syracuse, New York, and Morris Plains, New Jersey, virtually nothing is said about how these interiors advance a new model for domestic space, or how Craftsman furniture might support such a model. Moreover, no references to the voluminous scholarship on Progressive-era ideas about domestic interiors and their symbolism are found either in the body of the essay or in the footnotes. Without such a background, the authors cannot hope to support their suppositions. Moreover, as in the Brandt essay, the material covered is quite tangential to the interior designs shown in the Newark exhibition–a few photos of Craftsman Farms, illustrations from the Craftsman, and the 1903 model dining room.21 No images of Craftsman Farms appeared in the Dallas installation.

The final essay in the catalogue, by Joseph Cunningham, offers little that is new about Irene Sargent. The sparse footnotes, ignoring the fundamental work of scholars such as Cleota Reed, Marilyn Fish, and Mary Ann Smith (two of whom lived in Syracuse and pored through Sargent’s papers in the library there), contain so many “ibid.” references that one is hard pressed to find any awareness of the secondary literature in the text.22

The unhappy dichotomy between the exemplary quality of an important exhibition and the uneven scholarship in its companion book is not a new problem in the museum world. Moreover, in the search for new revenue following this punishing recession, and with changes in the business models of major public museums, other exhibition organizers have cut corners while making extravagant claims for their shows. Following trends that will reliably draw the public, museums such as the Art Institute of Chicago have also produced arts and crafts exhibitions that help to build credibility for their collections. The catalogue for Apostles of Beauty: Arts and Crafts from Britain to Chicago (on view from November 7, 2009, through January 31, 2010), also published by Yale University Press, contains five essays by staff curators at the host museum. The two senior curators are historians of American painting whose writing does not suggest deep reading on the decorative arts or architecture. Their three assistants, whose research is solid, are less secure as writers. The result is a book that looks beautiful, provides helpful information on individual artifacts, and makes extravagant claims for the importance of Chicago as the center of the arts and crafts movement in America with little to back them up. The Art Institute book conveniently excludes scholarship that does not support its point of view.23

Another catalogue, Inspiring Reform: Boston’s Arts and Crafts Movement (1997), which accompanied a fine exhibition organized by the Davis Museum at Wellesley College more than a decade ago, offers a stark contrast. Though expectedly more academic in tone, the lovely book places the achievements of Boston artists, architects, tradespersons, and writers in an international context. The team of scholars who contributed chapters is impressive, including Beverly K. Brandt, whose essay is superb and amply footnoted. The density of citations does not detract from the beauty of the book, as its design was carefully orchestrated by head curator Marilee Boyd Meyer to evoke the flavor of a fine offset press volume from the turn of the nineteenth century. Arts and crafts exhibition catalogues quite naturally lend themselves to fine book design, but few attain the quality of this one.24

Conclusion

Exhibitions celebrating collections of arts and crafts objects are still popular and will no doubt continue to draw large crowds for museums throughout the United States. As Lisa Konigsberg has proven with her “Initiatives in Art and Culture” programs, tours and scholarship in regional venues also contribute to a better understanding of the movement and its material culture production.25 There continues to be a tension between arts and crafts collectors, academic researchers, and museums, both public and private. When museums publish “research” that resembles the kind of rhetoric that one finds in auction catalogues, or neglect standards of scholarly documentation and protection of intellectual property, this tension only increases. One hopes that in the future institutions like those in Dallas and Chicago will more carefully monitor the relationship between their research and what has been published by academics under the standards of peer review that are commonly accepted in scholarly journals.

Gustav Stickley and his design colleagues at the Craftsman Workshops were indeed “apostles of beauty” during a period of idealism and reform in America. Their achievements have been aptly celebrated in the Dallas Museum’s exhibition, and Kevin Tucker deserves credit for organizing a major retrospective on furniture and decorative arts. I doubt that any Craftsman devotee would be disappointed with the objects or the installation of Gustav Stickley and the American Arts and Crafts Movement. Unfortunately, similar standards of care and quality are not found in the catalogue for this exhibition, raising important questions about the relationship between original research and museum practice during a challenging period for art museums everywhere.

Mark Alan Hewitt, FAIA, is a practicing architect, historian, and educator living in Bernardsville, New Jersey. A noted authority on American architecture, he is the author of six books and many articles on that subject. His latest book, written with Gordon Bock, is The Vintage House: A Guide to Successful Renovations and Additions (Norton, 2011).

- 1. Stickley’s only rival for this honor is Elbert Hubbard (1856 or 1857–1915), the eccentric New York soap salesman, publisher, writer, and entrepreneur who founded the Roycroft Colony in East Aurora, New York. Hubbard’s tragic death and limited output have diminished his historical importance somewhat, but his influence was wide.

- 2. See, for instance, David M. Cathers, “The Craftsman Designs of M. Lamont Warner,” Style 1900 9, no. 3 (Summer–Fall 1996): 38–41. On the origins of the movement and a chronology, see Robert Judson Clark, The Arts and Crafts Movement in America, 1876–1916 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1972), 9–13.

- 3. The first, “New Furniture,” appeared at the end of 1900; the second, “Chips from the Workshops of Gustave Stickley,” appeared in 1901. Both have been reprinted in Stephen Gray, ed., The Early Work of Gustav Stickley (Philmont, N.Y.: Turn of the Century Editions, 1996).

- 4. Mary Ann Smith, Gustav Stickley: The Craftsman (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1983); Barry Sanders, A Complex Fate: Gustav Stickley and the Craftsman Movement (Washington, D.C.: Preservation Press, 1996); David M. Cathers, Gustav Stickley (New York: Phaidon, 2003).

- 5. The best account of the bankruptcy is in Cathers, Gustav Stickley, 201–202.

- 6. The best sources on the Stickley family are by Marilyn Fish: Gustav Stickley: Heritage and Early Years (North Caldwell, N.J.: Little Pond Press, 1997) and Gustav Stickley, 1884–1900 (North Caldwell, N.J.: Little Pond Press, 1999).

- 7. See Joseph Bavaro and William Mossman, The Furniture of Gustav Stickley (New York: Van Nostrand, 1984); A. Patricia Bartinique, Gustav Stickley, His Craft (Parsippany, N.J.: Craftsman Farms Foundation, 1992); Donald A. Davidoff, “Sophisticated Design: The Mature Work of Gustav Stickley,” Antiques and Fine Art 7, no. 1 (December 1989): 84–91; “Davidoff, Maturity of Design and Commercial Success: A Critical Reassessment of the Work of L. & J. G. Stickley and Peter Hansen,” in Bert Denker, ed., The Substance of Style: Perspectives on the American Arts and Crafts Movement (Winterthur, D.E.: Winterthur Museum / Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 1996), 161–183; David M. Cathers, Furniture of the American Arts and Crafts Movement, rev. ed. (Philmont, N.Y.: Turn of the Century Editions, 1996); Barry Sanders, “Gustav Stickley: A Craftsman’s Furniture,” Art and Antiques 2, no. 4 (1979?): 46–53.

- 8. For an exploration of American-European cross currents in arts and crafts design, see Robert Judson Clark and Wendy Kaplan, “Arts and Crafts: Matters of Style,” in Kaplan, ed., The Art That Is Life: The Arts and Crafts Movement in America, 1875–1920 (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1987), 78–100. The authors note that Harvey Ellis, and perhaps Stickley as well, were conversant with art nouveau, secessionist, Jugendstil, and other Continental trends in interior design just after 1900.

- 9. Cathers’s Furniture of the American Arts and Crafts Movement is the standard source.

- 10. See, for instance, Gwendolyn Wright, Building the Dream: A Social History of Housing in America (Cambridge, M.A.: MIT Press, 1983), 162–164; Robert Guter and Janet Foster, Building by the Book: Pattern Book Architecture in New Jersey (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1992): 196–208.

- 11. Mark Alan Hewitt, Gustav Stickley’s Craftsman Farms: The Quest for an Arts and Crafts Utopia (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 2001).

- 12. Cathers, Gustav Stickley, 21–23, mainly on Dietrich; Ray Stubblebine, Stickley’s Craftsman Homes (Salt Lake City, U.T.: Gibbs Smith, 2006).

- 13. Thanks to Cheryl Robertson for pointing this out to me.

- 14. Tucker mentions Cathers in notes 1 and 2, averring that “David Cathers’s book stands as the definitive exploration of Stickley’s entire career.” Such a claim is doubtful, and would not be supported by Cathers himself, given the scope of Stickley’s creative work. Tucker uses this flimsy blanket citation to avoid mentioning any pertinent scholarship throughout his article, citing Cathers again in notes 49 and 51. The only other scholars noted are Eileen Michels and Jeanne R. France, on Harvey Ellis. Material that strikingly parallels his analysis can be found in Hewitt, “Art, Design and Technology,” in Gustav Stickley’s Craftsman Farms, 172–182; as well as Robert Edwards, “The Art of Work,” in Kaplan, The Arts and Crafts Movement in America, 223–235. Analysis of Stickley’s methods of joinery appears in Mark Taylor, “Commentary: Joinery and Construction,” in Bartinique, Gustav Stickley, His Craft, 84–85. Tucker also fails to cite the important work of Michael J. Ettema, “Technological Innovation and Design Economics in Furniture Manufacture,” Winterthur Portfolio 16 (1991): 197–223, which chronicles the development of woodworking machines in the late nineteenth century.

- 15. A scholar whose work continues in this area is Eileen Boris, who first treated “the new industrialism” in her Temple University dissertation. See Boris, Art and Labor: Ruskin, Morris and the Craftsman Ideal in America (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1986); and Boris, “Dreams of Brotherhood and Beauty: The Social Ideals of the Arts and Crafts Movement,” in Kaplan, The Art That Is Life, 208–222. Needless to say, Tucker makes no mention of her work.

- 16. See Stubblebine, preface and introduction to Stickley’s Craftsman Homes, xi–xiv.

- 17. Brandt reviewed my book in the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians (61 [March 2002]: 97–98) and thus was familiar with my analysis, which appears on pages 148–172. As she states in the review, “Hewitt’s ‘complex parable’ uncovers many paradoxes that scholars reading this study will continue to ponder.” Her title considers one of these but makes no reference to my book. It is perplexing to find that the characteristics of the Craftsman house that are clearly cited both in my book and in Stickley’s published writings do not appear in Brandt’s essay. Her brief section “Features of the Craftsman Home,” on pages 72–73, discusses “contextuality” and bungalow types but ignores the essential article “Distinguishing Features of the Craftsman House,” Craftsman vol. 23, n. 6 (March 1913): 727–29. The articles from the Craftsman cited by Brandt are randomly selected from a huge number of pieces presenting individual designs, all of which are referenced in Stubblebine, Stickley’s Craftsman Homes. Moreover, none of Stubblebine’s articles on the subject appear in Brandt’s essay, including Stubblebine, “Gustav Stickley’s Craftsman Home,” Style 1900 9, no. 2 (Spring/Summer 1996): 22–25; and Stubblebine, “In Search of Craftsman Homes,” Old House Journal (July/August 1996): 27–33.

- 18. Cheryl Robertson, “Male and Female Agendas for Domestic Reform: The Middle-Class Bungalow in Gendered Perspective,” Winterthur Portfolio 16 (Summer–Fall, 1991); Arlette Klaric, “Gustav Stickley’s Designs for the Home: An Activist Aesthetic for the Upwardly Mobile,” in Patricia A. Johnson, ed., Seeing High and Low: Representing Social Conflict in American Visual Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006): 177–193; Dolores Hayden, The Grand Domestic Revolution: A History of Feminist Designs for American Homes, Neighborhoods, and Cities (Cambridge, M.A.: MIT Press, 1981).

- 19. See Tommy and Beth Ann McPherson, “The Furniture,” in David Cathers, ed., Craftsman Farms: A Pictorial History, 2nd ed. (Philmont, N.Y.: Turn of the Century Editions, 2010).

- 20. Stickley’s influence on interior design is cited in virtually every book on American houses covering the early twentieth century. A good example is Clifford Edward Clark Jr., The American Family Home, 1800–1960 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986), 146–152. For specific treatment of how Craftsman furniture and interiors are related, see David Cathers and Alexander Vertikoff, Stickley Style: Arts and Crafts Homes in the Craftsman Tradition (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999). The authors go into great detail about each room in the house and how furniture should relate to its function and elements.

- 21. As a former president of the Craftsman Farms Foundation, which runs the Stickley Museum, I was disappointed that so little from this important site was included in the exhibition. The small group of photos hung in Newark and cursory description was tantalizing but ultimately better left out of the show. This would also have made the McPhersons’ essay unnecessary.

- 22. The fundamental work on Sargent appears in Smith, Gustav Stickley, 34–37. Analysis of her contribution to the theories that supported Craftsman production awaited the work of Cleota Reed. See Reed, “Irene Sargent: Rediscovering a Lost Legend,” Courier 16 (Summer 1979): 3–13; Reed, “Irene Sargent: A Comprehensive Bibliography of Her Published Writings,” Courier 18 (Spring 1981): 9–25; and Reed, “‘Near the Yates’: Craft, Machine and Ideology in Arts and Crafts Syracuse, 1900–1910,” in Denker, The Substance of Style, 359–374. Reed follows the same line taken by Cunningham, citing more primary sources than appear in his 2010 essay. In addition, Marilyn Fish has written about Sargent’s editorial slant and contributions to the Craftsman in The New Craftsman Index (Lambertville, N.J.: Arts & Crafts Quarterly Press, 1997), 15–21. As in the previous pieces in the catalogue, virtually nothing but primary source material appears in the footnotes, despite a marked interpretive similarity to the secondary sources above.

- 23. Judith A. Barter, ed., Apostles of Beauty: Arts and Crafts from Britain to Chicago (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago/New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009).

- 24. Marilee Boyd Meyer, ed., Inspiring Reform: Boston’s Arts and Crafts Movement (New York: Harry N. Abrams: 1997).

- 25. For instance, “Regionalism and Modernity: The Arts & Crafts Movement in San Diego and Environs,” held June 24–27, 2007.