Exhibition:

The Bauhaus in Calcutta: An Encounter of the Cosmopolitan Avant-Garde

Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau, Dessau, Germany

March 27 – June 30, 2013

Catalogue:

The Bauhaus in Calcutta: An Encounter of the Cosmopolitan Avant-Garde

Edited by Regina Bittner and Kathrin Rhomberg

Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2013.

212 pp.; 132 ills.

Softcover €35.00

ISBN: 9783775736572

The meeting of Dickens and Dostoevsky is the stuff that dreams are made of, revealing the essence of one great figure refracted through the lens of another. That particular episode was only a dream—revealed in last April’s TLS as a literary hoax—but this type of story is all the more irresistible because it sometimes turns out to be true. The encounter between artists of the Bauhaus and the Bengali avant-garde at the Fourteenth Annual Exhibition of the Indian Society of Oriental art, held in Calcutta in 1922, has long tantalized scholars of South Asian modernism. And yet, it was not until last spring, when an exhibit at the Bauhaus in Dessau, Germany, displayed the results of an extensive archival investigation, that the world gained its first glimpse at this cosmopolitan avant-garde that never quite got off the ground.

In its early years, the Weimar Bauhaus was largely shaped by the Swiss painter and pedagogue Johannes Itten, who was responsible for the school’s foundational course. Together with his colleagues, Itten believed that traditional academic art was stagnant and corrupt, capable of imitating only itself, and bearing no relation to the world outside the studio. In order to break free of these conditions, he emphasized practices derived from contemporary Viennese psychology designed to cultivate the student’s innate creative abilities. A favorite among Bauhaus students, Itten has remained a challenge to subsequent interpreters, too easily reducible to his shaven head and monk’s robes. And yet, his interests in esoteric subjects such as theosophy, Mazdaznan spirituality, and the development of individual creative expression were responses to a very real situation of cultural and educational discontent. And he was not alone. His work found affinities with other artists disenchanted with academicism in a network stretching as far as India.

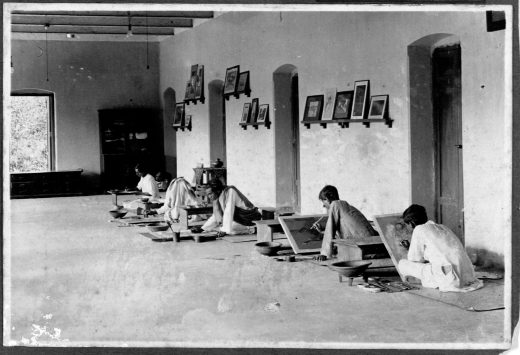

For many Indian artists, academic art had an additional problem: it sprang from a European tradition based on European standards of beauty, representation, and technique. In the same year as the Bauhaus’s founding, a similar educational project came to fruition outside Calcutta at Shantiniketan. Using the prize money from his 1913 Nobel Prize in Literature, Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore set up a university whose comprehensive vision united not just the fine and applied arts, but also the study of philosophy and agriculture. By holding classes outdoors, Tagore attempted to integrate his school into the community, and hoped to create a model of economic and cultural renewal that could create a new India. It is these shared visions and affinities that the Bauhaus in Calcutta exhibition sought to explore.

Located in Dessau, a small industrial town ninety minutes from Berlin by commuter rail, the Bauhaus building, home of the school after 1925, has sustained much damage over the years. The simple modernist complex designed by Walter Gropius stands as a symbol of the second, more famous iteration of the school, and is currently open to visitors as an architectural shell. The Bauhaus in Calcutta exhibition occupied two rooms on its second floor. Like the building itself, the exhibition space was sparse and almost forensic. Strikingly, there were almost no objects in the first of the exhibition’s two rooms; instead, paper material was laid flat on low green baize tables. The room was organized primarily around cities: Weimar, Berlin, Calcutta, London, and Vienna. As the visitor moved through the space, thematic text panels provided nodes for clusters of information. Photographs, letters, and invoices—or merely photocopies of them—formed a network of mundane paperwork inside the great white archival box of Gropius’s building. Accompanying this paper trail, small cube televisions played interviews with scholars of South Asian art. This layout enabled a synoptic view of the connections between historical figures, of a sort that is often absent from scholarly essays. It showed that, even without objects, an exhibition can excel over purely verbal media simply through the spatial arrangement of text and image. In this way, the Bauhaus in Calcutta did not present merely “spiritual alliances” between the Bauhaus and Shantiniketan programs, but actual relationships, friendships, correspondence, and in-the-flesh meetings which reveal how globally intertwined the movements really were.

Central to this story was the young Austrian art historian Stella Kramrisch, who had studied under Josef Stryzgowski at the University of Vienna. Stryzgowski, somewhat unexpectedly, had connections to both the Bauhaus and to Tagore (the latter through William Rothenstein, whose London-based India Society sponsored the English translation of Tagore’s prizewinning poem Gitangali). Kramrisch’s teacher helped her secure a visa to India after Tagore invited her to teach Art History at Shantiniketan and to help organize the exhibition for the Oriental Society. Kramrisch likely knew Itten from Vienna, where he had operated a private art school prior to his appointment at the Bauhaus, and wrote to him requesting works from the school for the 1922 exhibition. Though Kramrisch is better known for her later writings on the ancient arts of South Asia, becoming a curator at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in the 1950s, her involvement with the Bauhaus in the1920s is a reminder both of the breadth of her interests, and of those of the early Bauhaus under Itten.

With all the contextual and historical material set out in the first room of the exhibition, the second room, which contained only unlabeled paintings, was able to resonate with a richer set of references. Visitors to Dessau, like the original viewers in Calcutta, were encouraged simply to look, to compare, and to draw one’s own conclusions. Georg Muche’s woodblock-style prints and Sunyani Devi’s hazy miniature-style paintings both reinterpreted traditional techniques. The watercolors of Gaganendranath Tagore (Rabindranath’s nephew) assumed a strong three-dimensional quality through the juxtaposition of blocks of black and white, a technique similar to that employed by European cubists, to emphasize the tension between pictorial depth and the painting’s two-dimensional surface. While Tagore’s paintings exhibited a serene, deepening sense of movement, Lyonel Feininger’s abundance of lines created a frenetic energy. However, unlike the original 1922 exhibition, which showed the Bauhaus and Bengali works in different sections (along with a third category of “international” works), the Dessau exhibition emphasized the comparison even more by hanging all the works together: paintings by Abanindranath Tagore (another nephew) next to those by Itten, Gerhard Marcks’s next to Nandalal Bose’s. This introduced a variety of visual styles, even within each group, but most of the artists seemed to be responding to two major issues: the newly problematic relationship to artistic tradition, and questions of the relative merits of appearance versus essence in visual representation. Breaking away from academic practice, many Bauhaus artists experimented with representing motion and the spirit rather than nature as we see it. About a decade before this exhibition, some colonial critics had declared that a tradition of fine art (in the European sense) did not exist in India, because Indian art did not conform to the principles of naturalistic representation. Kramrisch critiqued this view, holding up the Bauhaus works as examples of non-naturalistic European art.

The curators of the Bauhaus in Calcutta framed the Fourteenth Annual Exhibition of the Indian Society of Oriental Art as an encounter between two developing movements seeking inspiration from each other. In fact, Tagore and Itten themselves saw dialogue as an essential requirement for the development of culture; without it, culture would become insular, stagnant, and intolerant. Tagore, who gave his school the motto yatra viśvam bhavatyekanidam (where the world makes a home in a single nest), thought that Shantiniketan was a place for mutual exchange of ideas, where India could share its wealth of tradition with the world, and where she would benefit from learning about international trends.1 Ironically, the Bengali artists did not seek much of their foreign inspiration from the contemporary West. Instead, Far Eastern art was a much stronger influence on their visual style.

For his part, Itten thought of India not only as a place of spiritual and creative power, but also—in contrast to the view of many contemporary Indian writers—as one uncorrupted by the forces of industrialization and rationalization that had created a rift in Western culture. For him, Indian culture and spirituality could offer the West a model for infusing art with spirit, counteracting materialist tendencies. Unfortunately, the Bauhaus in Calcutta exhibition stopped short of considering the subsequent histories of the two movements. As the Bauhaus continued to develop, Itten’s ideas clashed with Gropius’s vision of a more socially and technologically engaged artist, leading to Itten’s resignation just a year after the 1922 Calcutta exhibition. Gropius, along with a new staff that included Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and Josef Albers, redefined the institution, ridding it of Itten’s vision of the union of art and spirit and insisting instead on the union of art and technology. This also meant severing the close ties with India and Eastern thought that Itten had brought with him. The Fourteenth Annual Exhibition was not necessarily meant to be an anomaly, but instead represents a particular vision of global artistic and cultural communication that was abandoned.

The Bauhaus in Calcutta was a modest exhibition, but what the curators pieced together from archives in Europe and India will have a lasting importance beyond those two small rooms eighty miles south of Berlin. The accompanying book of essays, The Bauhaus in Calcutta: An Encounter of the Cosmopolitan Avant-Garde, should be more widely disseminated. This valuable resource, which offers additional interpretation by some of the world’s leading scholars, nonetheless lacks the exhibition’s simple, well-articulated layout of relationships between individuals, institutions, and cities, a structure that provides researchers with a blueprint for the future study of a cosmopolitan avant-garde in the process of its formation. Although the Bauhaus in Calcutta exhibition finally answered many basic questions about the legendary meeting of the Bauhaus and the Bengali avant-garde, it was equally exciting because of the number of questions that still remain.

Antonia Behan is an M.A. candidate at the Bard Graduate Center. Previously, she studied Sanksrit at the University of Toronto.

- 1. The translation is that given by Visva-Bharati University (http://visva-bharati.ac.in/at_a_glance/at_a_glance.htm). The Sanskrit verse is from the Yajurveda (32:8).

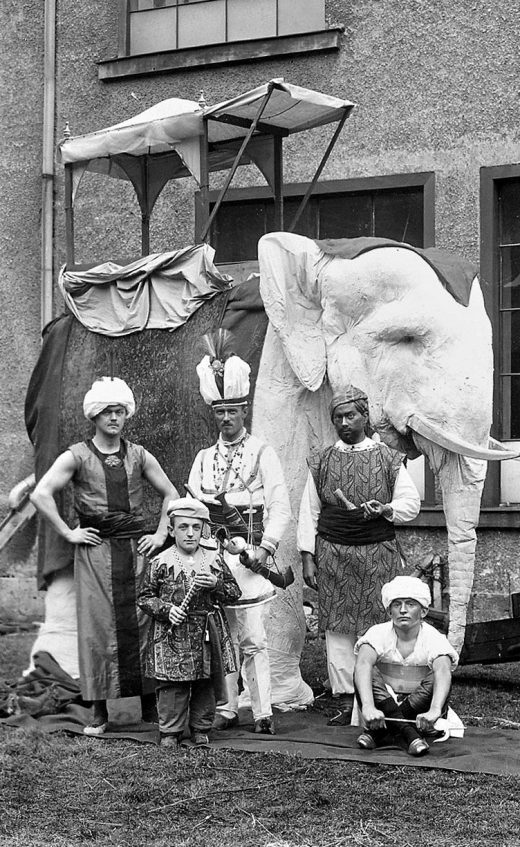

Members of the Indian Society of Oriental Art. Photo: Journal of the Indian Society of Oriental Art, 1981. All images provided by the Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau Press Office.