Jim Henson, Paperwork Explosion (1967)

“The government’s laws and orders will be transmitted to the furthest reaches of the social order with the speed of electric fluid.”1 Such was the promise made by the chemist, industrialist, and minister of the interior Jean-Antoine Chaptal in 1800. It could be said to signal a shift in the West’s way of thinking about official recordkeeping. The idea of the paperless office was born.

Media historians have long recognized the astounding versatility, portability, and durability of paper, which is in many respects the ideal material support. As a corollary, the paperless office has been dismissed as a “myth” by social scientists, information engineers, and corporate consultants alike, who predict that paper’s many affordances will continue to make it indispensable.2 And a myth it is, but not (or at least not only) in the simple sense typically employed in these contexts. The paperless office should also be interpreted as a myth in the Lévi-Straussian sense of the term, that is to say, an imaginary resolution to real contradictions.

What contradictions? We get a preliminary idea by examining a remarkable little film, The Paperwork Explosion (1967). Commissioned by IBM, the film was directed by a little-known experimental filmmaker named Jim Henson and scored by Raymond Scott, the composer and inventor who wrote most of the tunes behind Looney Tunes, introduced the first racially integrated network studio orchestra, and pioneered electronic music with such technologies as the Orchestra Machine, the Clavivox, and the Electronium. Henson and Scott’s collaboration explains, no doubt, the film’s considerable formal intelligence and diegetic wit.3

The film promotes the IBM MT/ST, a machine released in 1964 combining the company’s Selectric typewriter with a magnetic tape disk. Operators entered text and formatting codes onto magnetic tape; they could then make simple changes before printing a clean copy of the document. More advanced versions of the machine included two tape drives, allowing for mail merge and similar features. Among historians of computing, the MT/ST is best known as the first machine to be marketed as a “word processor” (a term that, as Thomas Haigh has pointed out, emerged at the same moment as Cuisinart’s “food processor”).4

The IBM film opens with an extraordinary montage of the history of media and communication: scribes and printing presses, watermills and assembly lines, container ships and spacecraft. This montage is interrupted by the sound of brakes squealing and the image of a car swerving towards the viewer. Cut to a rural scene, the sound of chickens, an old man with a corncob pipe. “Well,” he says. “You can’t stop progress.” A quick glimpse of a subway train before a man who looks like he must be an engineer of some kind tells us “It’s not a question of stopping it so much as just keeping up with it.” An image of a jetliner before another talking head — thick frames, thin tie — tells us that “At IBM our work is related to the paperwork explosion.” Suddenly stacks of paper on a desk explode into the air and sail through a blue sky. Another voice tells us “specifically, paperwork in an office,” while paperwork explodes in the figurative sense, spilling out of desks and drawers. Then a repeat of the literal explosion. “Paperwork explosion” a voice says.

We are not quite one minute into the five-minute film. Faces of office workers appear one after the other to tell us that “There’s always been a lot of paperwork in an office — but today’s there more than ever before — there’s more than ever before — certainly more than there used to be!” This last statement is spoken by the old farmer, whose folksy observation also concludes the next montage: “In the past, there always seemed to be enough time and people to do the paperwork — there always seemed to be enough time to do the paperwork — there always seemed to be enough people to do the paperwork— there always seemed to be enough time and people to do the paperwork — but today there isn’t.” The pulse of Raymond Scott’s electronic music accelerates as more faces speak to us of their struggles with paperwork: “Today everyone has to spend more time on paperwork: management has to spend more time on paperwork — secretaries have to spend more time on paperwork — companies have to spend more time on paperwork — salesmen — brokers — engineers — accountants — lawyers — supervisors — doctors — executives — teachers — office managers — bankers — foremen — bookkeepers — everybody has to spend more time on paperwork.” Once again we see a shot of paperwork exploding. The farmer: “Seems to me we could use some help.”

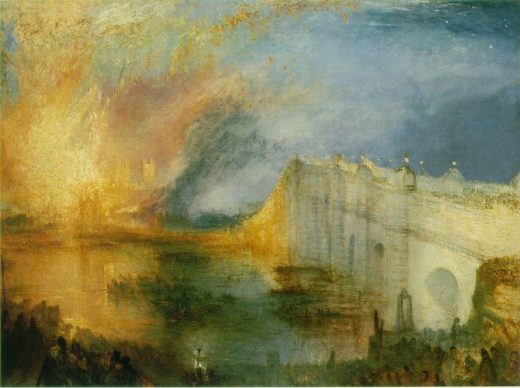

The Paperwork Explosion takes its place in a long history of images of paperwork combusting. This history might begin with J.M.W. Turner’s two brilliant canvases Burning of the Houses of Parliament (1835).

These fires weren’t sparked by paperwork, exactly, but by the notched wood sticks used for some eight centuries by the Exchequeur’s office to record receipts and expenditures. As Charles Dickens recounted twenty years later: “The sticks were housed in Westminster, and it would naturally occur to any intelligent person that nothing could be easier than to allow them to be carried away for firewood by the miserable people who lived in that neighborhood. However, they never had been useful, and official routine required that they should never be, and so the order went out that they were to be privately and confidentially burned.”5 The sticks were thus unceremoniously fed to a furnace in the basement of the House of Lords on October 16, 1834. They took their revenge, however, by taking the Houses of Lords and Commons with them into the flames. Turner’s paintings depict the accident in delirious detail.6

Think also of the paperwork explosion that opens the narrative of Fassbinder’s The Marriage of Maria Braun (1979). As the film opens, we hear bombs falling and watch a wall collapse to reveal a wedding in progress. The bride and groom and guests scramble to get out of the Civil Registry Office as women scream and babies cry and hundreds and hundreds of documents tumble through the air. “Sign here! Put a stamp on it!” Maria Braun yells to the Nazi official as they lie on the ground. The image reappears several years later in Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985), as Robert De Niro’s character vanishes beneath with paperwork falling from the sky following the destruction of the Ministry of Information.

“IBM can help you with the time it takes to do the paperwork,” the film continues. We see sexy shots of machines as voices offscreen tell us that “With IBM dictation equipment I can get four times as much thinking recorded as I can by writing it down…” The voices continue to explain the various features and benefits of IBM office equipment: cordless dictation, error-free copy, improved typography, increased productivity. “IBM machines can do the work — so that people have time to think — machines should do the work — that’s what they’re best at — people should do the thinking — that’s what they’re best at.” Once again the music accelerates as a series of faces and voices speed across the screen: “Machines should work — people should think — machines — should work — people — should think — machines — should — work — people — should — think.”

* * *

The “paperwork explosion” expresses both a threat and a wish. The threat, of course, is that we are being overwhelmed by paperwork’s proliferation, its explosion — a threat that historian Ann Blair has recently traced through the early modern period.7 The wish is to convert all this cumbersome matter into liberating energy, which is exactly what explosions do. From Chaptal’s “electric fluid” to IBM’s “Machines Should Work, People Should Think” to USA.gov’s “Government Made Easy,” we remain attached to the idea that someday, somehow, we can liberate this energy, put it to other uses.

Significantly, in this film, the liberation of this energy ends up being the liberation of labor. This becomes apparent at the very end, when we discover that our farmer is not exactly a farmer after all, but has returned from the future to deliver his message. “So I don’t do too much work anymore,” he tells us. “I’m too busy thinking.” The camera fades to black as a harmonica plays gently in the background in striking contrast to electronic pulses and clattering machinery that have provided the soundtrack so far. In the future, machines work while people think. This is the old utopian dream of a government of men replaced by the administration of things (or of bits of data). This is man who has been hunting in the morning, fishing in the afternoon, herding in the evening, philosophizing after dinner, surfing the web late into the night, without having become a hunter, fisherman, herdsman, philosopher, or coder. This is man unalienated. Not bad results from a business machine.

Yet we must not miss the ambiguity here. “Machines should work, people should think.” The message repeats itself several times; it’s the core of the film’s techno-utopian vision. We can imagine IBM executives and lawyers and public relations agents sitting across a table from Jim Henson telling him to make sure he includes these lines in his film. What if, following William Empson’s advice to readers of poetry, we shifted the emphasis just a little bit? From “machines should work, people should think” to “machines should work, people should think”? Is it possible that the film might be trying to warn us against its own techno-utopianism? Read this way, the film is less an imaginary resolution to the problem of information overload in the modern era than an imaginative critique of this imaginary resolution. Machines should work, but they frequently don’t; people should think, but they seldom do.

Ben Kafka, a Contributing Editor for West 86th, is an assistant professor of the history and theory of media at NYU. His first book, The Demon of Writing: Powers and Failures of Paperwork, will be published by Zone Books in fall 2012.

- 1. Archives Parlementaires, 2eme série (Paris: Librairie administrative de P. Dupont, 1879-): I:230 (Session of 28 pluviôse an VIII).

- 2. The classic text is Abigail J. Sellen and Richard H.R. Harper, The Myth of the Paperless Office (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002).

- 3. I am aware of two slightly different versions of this film: one obtained from the IBM archives and another posted on YouTube by the Henson Company: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_IZw2CoYztk. The Henson version includes the opening montage; the IBM version doesn’t.

- 4. Thomas Haigh, “Remembering the Office of the Future: The Origins of Word Processing and Office Automation,” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing (October-December 2006); pp. 6-31.

- 5. Charles Dickens, “Administrative Reform: Theory Royal, Drury Lane, Wednesday, June 26, 1855,” in Speeches Literary and Social (London: John Camden Hotten, 1870), 132–133.

- 6. For a marvelous investigation of this incident, see Edward Eigen, “On the Record: J.M.W. Turner’s Studies for the Burning of the Houses of Parliament and Other Uncertain Bequests to History,” Grey Room 31 (Spring 2008); pp. 68-89.

- 7. Ann M. Blair, Too Much to Know: Managing Scholarly Information before the Modern Age (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010).