Queens Museum, New York City

March 8 – June 28, 2015

Arshiya Lokhandwala, independent curator and founder of the Lakeeren Gallery in Mumbai, has assembled a fascinating exhibition in two complementary parts that offers visitors to the Queens Museum in Flushing’s Corona Park a selective crash course in Indian art from independence to the present.

To show Indian artists’ engagement with international Modernism, she successfully appealed to private collectors in the New York area to lend examples of works by members of the Progressive Artists’ Group (active from 1947 to 1956) and some of their contemporaries. This was an era when painting still ruled, and artists left India, usually temporarily, for Paris and, increasingly, New York, several with the support of the Rockefeller Foundation. They sought stimulation from the School of Paris and emerging Abstract Expressionism. V. S. Gaitonde, for instance, drew inspiration from the works of Mark Rothko, with whom he became acquainted. In spite of their urge to work within European and North American internationalism, their best paintings retain a cultural peculiarity that is distinctively Indian. The abstractions by Ram Kumar derived from his visit to the holy city of Varanasi (Benares) on the banks of the River Ganga (Ganges) in the early 1960s are the high point of the first part of the exhibition. One canvas in particular sets bold, irregular blocks of rich blue and orange in a maze of earth colored forms infused with the fluidity of a Max Ernst.

If the anxiety of the painters of the Progressive Artists’ Group generation to be internationally relevant revealed itself in the adoption of European and North American Modernist conventions, that of the current generation represented in the second part of After Midnight shows how artists can address specifically Indian themes while yet conforming to the conventions of the global art market that allows their work to function in the successive biennials that dominate the international art world today. Anita Dube (fig. 1) has created a huge linear form on one wall incorporating the epigram familiar from Francisco Goya’s suite of etchings, Los Caprichos, “The sleep of reason creates monsters.” So far, so European; but each and every sinuous line of this 2001 work that constitutes the monster and its epigram is composed of individual enameled votive eyes of various sizes used in Hindu devotions. The sleep of reason to which Dube alludes has a specifically confessional cast, for the monster to which it gives rise is implicitly that of Hindu extremism responsible for the destruction of the Babri Mosque in Ayodhya in 1992, and other outrages that have subsequently led to huge loss of life.

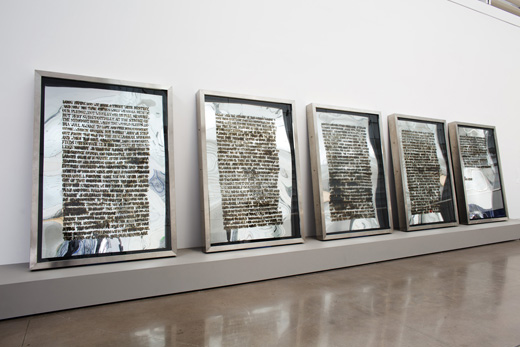

Equally political within a specific cultural nexus is the monumental work by Jitish Kallat, Public Notice (2003) (fig. 2). Kallat stenciled the entire text of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s speech given at midnight as India gained independence on August 14, 1947 in flammable adhesive onto five huge acrylic mirrors. When he set fire to the letters, burning them into the surface, the mirrors buckled. The resulting panels, each in a glazed heavy steel frame, recall the angry stenciled texts of African American artist, Glenn Ligon, but the resonance is specifically Indian. Nehru’s “Tryst with Destiny” speech has a cultural standing in that country equivalent to Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech of 1963 in the United States.

Mithu Sen can work on a large scale, too, but her piece in After Midnight is intimate. She has gathered a plethora of odd, small things, from plastic dolls to kitsch phalluses, in a dimly lighted cylindrical vitrine titled MOU (Museum of Unbelonging) 2 (2015). Some of the toys, keepsakes, and votive items are Western, others Indian. The juxtapositions are messy but deliberate: a votive eye like one of the thousands used by Anita Dube in The Sleep of Reason Creates Monsters is laid atop one of Albert Einstein’s in a print of the famous photograph of the physicist sticking out his tongue. A momentary irrational irruption of Western rationalism is itself overlaid by a token of Hindu irrationalism.

Most effective as a reminder of the lives of those millions who exist outside the immediate terms of Western rationalism and cupidity that contribute to the reduction of those millions to penury is a composite object that serves as an anti-monument, What does the vessel contain that the river does not? (2014) by Subodh Gupta (fig. 3). A real river rowboat is loaded beyond the gunwales with the useful things and detritus of a human life: soiled blankets, battered cooking vessels, a mattress, clothing, wire mesh, oars, pieces of charred wood with the smell of combustion still lingering. This is not an image of hopelessness, rather of the ingenuity of desperation that still far outweighs burgeoning high tech and middle-class prosperity in the world’s most populous democracy.

Several of the eighteen individual artists and collectives in the exhibition have had recent exposure in North America and on the international biennial circuit, but their work remains to a large extent little known to an American audience. Their cultural specificity is their strength: viewers would do well do attune themselves to Indian issues. After Midnight gives New Yorkers who take the Number 7 train to Mets-Willets Point that opportunity.

Ivan Gaskell is professor and head of the Focus Project at the Bard Graduate Center in New York City.