This review originally appeared in the Vol. 19 No. 2 / Fall-Winter 2012 issue of West 86th.

Exhibition:

Anglo-Saxon Hoard: Gold from England’s Dark Ages

National Geographic Museum, Washington DC

October 29, 2011–March 4, 2012

Catalogue:

Lost Gold of the Dark Ages: War Treasure, and the Mystery of the Saxons

By Caroline Alexander

Washington: National Geographic Society, 2011

256 pp.; 200 color photographs; 3 maps

Cloth $35.00

ISBN: 1426208146

One of the most invigorating elements of studying the material culture of the early Middle Ages is that the field continues to expand in a very real way: hundreds of new objects have come to light in recent years. This was particularly true during the boom of the early 2000s, which saw archaeological surveys throughout Europe for building and infrastructure projects, but the work of amateur enthusiasts with metal detectors has been a major source of discovery, too. When it was announced in September 2009 that a detectorist had uncovered a very large hoard of Anglo-Saxon metalwork, the news excited the public nearly as much as it did scholars. The Staffordshire Hoard, as it was dubbed, encompassed over 3,500 separate items, comprising 5.094 kilograms of gold (over three times more than was discovered at the famous Sutton Hoo site), 1.442 kilograms of silver, and thousands of garnets: it was truly a spectacular find. After exhibitions in Birmingham, Stoke-on-Trent, and London, staged in part to inspire public support for the purchase of the hoard by two museums in England, select items travelled to the National Geographic Museum in Washington, DC, for their sole American appearance. Clearly conceived as a popular exhibition, this public presentation of the Staffordshire Hoard nonetheless raises interesting questions about how we relate to things of the past and how they relate to us.

A visitor to the exhibition first finds himself in a narrow space with faux shields painted on the walls and, more conspicuously, large and rather loud projected images of Anglo-Saxon warriors at battle, as portrayed by modern reenactors. Most scholars will immediately feel their skepticism rise: the hoard looks to be captive to an imaginative medievalism of the present-day, and the chance of a real examination of the objects outside such fantasies seems slim. The question of how the show will present its materials is further complicated by the next room, which first meets the visitor with a case containing a leather satchel with small gold objects falling out of it, accompanied by no information save a line from Beowulf: “hurry to feast your eyes on the hoard.” But such a feast has not been laid, for next one sees two large photographs of white-haired, portly men: Terry Herbert, the metal detectorist who discovered the hoard, and Fred Johnson, owner of the farm which yielded the gold. From the outset, then, the narrative of the exhibition is tangled: Is it about Anglo-Saxon England? Is it about treasure hunters? Is there any chance it will be about the actual artifacts in the hoard?

Happily, the distracting nature of the first rooms does not extend to the core of the exhibition, a large, open-plan room featuring focus displays on particular objects and groups of objects from the hoard. Whereas the video and graphics of the first rooms distracted from the objects, here they focus your attention: a short video showing how garnets were cut and set by Anglo-Saxon smiths, again shot with reenactors, is exemplary in its clarity and attention to detail. These videos, created with the significant involvement of the living-history society Regia Anglorum, are a fine testament to the potential benefits when amateur enthusiasts work with trained scholars to create vivid images of the past. When viewed again with this perspective, in fact, the introductory video looks a lot better: the costume, weaponry, and regalia are expertly made, and they cast familiar museum pieces (such as items from Sutton Hoo) in the real world of their initial use. Some of the modern reconstructions from the videos, such as a sword and processional cross, are included in the exhibition and serve well to help visitors understand how certain fragments from the hoard might fit together. Touch-screen displays accompanying select objects allow the visitor to view the pieces from several different angles and investigate their details and possible meanings more carefully, again giving fuller sense of what these things are and were. Since many of the objects are small, and appear smaller still in capacious display cases, these alternate presentations allow visitors different points of access to the objects.

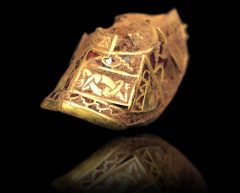

It is striking that, even in the face of an extensive interpretive apparatus—encompassing graphics, reconstructions, and audio, video, and computer modules—the objects themselves remain undoubtedly the star of the show. They are small and mangled, they are fragments and often themselves fragmented, yet they have remarkable pull. As I watched and eavesdropped on other visitors, it was clear that even casual beholders were subject to their charms. The gold-lust they inspire is very real, and the objects have been presented, both in the images provided to the media and in the exhibition, to maximize that effect. In the display cases, they are brilliantly lit and set against rich fabrics, while the images distributed to the media (and illustrating the exhibition) have clearly been carefully manipulated to make the objects pop.

The desire to emphasize the hoard’s status as “treasure” has been a crucial component of its presentation and reception from the very first.1 The hoard was, of course, discovered not by an archeologist but by a treasure hunter, and the payout that Herbert and Johnson received from the British government for the hoard is mentioned in nearly every comment on the find. The compulsory sale of the objects to public collections is an element of the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS), a government program which requires and encourages members of the public to report any finds of gold and silver objects over three hundred years old, as well as prehistoric base-metal assemblages. While the general consensus has been that the PAS has been a great success, resulting in the tracking of 764,861 artifacts at last count, there has been some concern, primarily expressed informally, that the emphasis on the material benefit Herbert and Johnson derived from the find will result in something of a gold rush across the English countryside. Detectorists are by and large not trained in proper archaeological excavation and documentation, and the desire for a big strike may lead to hasty and careless excavations. Indeed, the excavation of the Staffordshire Hoard site subsequent to Herbert’s discovery has come under serious criticism, with some archeologists charging that it was conducted hastily with more of an eye to maximizing public relations impact than methodical record keeping.2 The blurred distinction between historical artifact and modern-day treasure might prevent us from gaining any real insight into the culture in which such objects were made.

In part due to the as-yet inconclusive archaeological surveys of the find spot, no satisfactory explanation for the origins of the hoard or the reasons for its deposit in the ground has yet been put forth.3 In a video documentary accompanying the exhibition, Kevin Leahy, National Finds Adviser of the Portable Antiquities Scheme, muses: “[The Staffordshire Hoard] doesn’t have a context. Its context is itself.” Whether intentionally or not, Leahy articulates the core problem that the exhibition and accompanying publication by Caroline Alexander are unable to solve: How, exactly, are we to imagine the Staffordshire Hoard? As described above, the first rooms of the exhibition put forth three different answers in quick succession: the objects are war regalia, they are the contents of a leather satchel (whose intended destination is unknown), and (or?) they are a lucky find. The exhibition succeeds best in answering the question in the main room, where it focuses on individual pieces and groups of like objects, but it falters again in later rooms as it attempts to create something of a broader context by including components about Old English poetry and cultural change in Anglo-Saxon England. Alexander’s book, though engagingly written and beautifully illustrated, similarly attempts to shed light on the objects by conjuring the social and cultural changes of the early Anglo-Saxon period, but the things themselves end up buried in context, to be excavated again only in an appendix of beautiful but sparsely annotated photographs.

The anxiety of context continues to vex many curators and art historians: How can we properly consider objects within their historical setting while allowing for the very real presence they have in the present day? The Staffordshire Hoard brings this question into sharp relief because the narrative of its discovery powerfully amplifies the beauty and mystery of its contents. There is a clear sense, in the fitful attempts to interpret and contextualize the objects, that their mysteriousness is to be understood as an essential part of their nature. Consider how most of the objects are reproduced (fig. 1): against black backgrounds, conjuring memories of the rich soil from which they were unearthed, but with digitally inserted “reflections,” hinting at something left behind, unknown and only dimly glimpsed. We literally see them in a mirror, darkly. This photoshopped conceit must be rooted in part in the popular conception of the early medieval period as the “Dark Ages,” but I think it also accentuates our sense that objects have an inner life that we can only imagine.4 This intuition is brought out in the nearly contemporary Old English riddles, in which things speak of themselves enigmatically. One riddle, for example, intones

My race is old, my seasons many,

My sorrows deep . . .

. . . I remember

who ripped our race, hard from its homeland,

stripped us from the ground. I cannot bind

or blast him, yet I cause the clench of slavery

round the world . . .5

It is gold who speaks here, and as in many of the other riddles that conjure metals and precious stones, gold seems to mourn for its lost origins in the earth. In the exhibition, the objects are constantly being excavated and cleaned in photos and videos; one touch-screen program allows visitors virtually to brush the dirt off a star-shaped mount. The narrative of these objects as born of, returned to, and resurrected from the earth is constantly present. But their histories encompass much more: nearly all the materials in these objects were recycled. Gold was not mined in the British Isles at this time, so new gold objects needed to be made from recycled materials. X-ray fluorescence analysis of the garnets revealed that while some of them came from Bohemia, the larger cabochons originated in Sri Lanka, and almost certainly came to England through Roman trade networks. Each of these objects thus has the memory of previous forms within them.

The Staffordshire Hoard is, in many ways, a construction of the early twenty-first century. For the foreseeable future, scholars interested in the objects that have been forged together into this new collective identity will have to keep the particular nature of its construction firmly in mind. Far from being a barrier, however, I think this provides an important opportunity to analyze objects as existing in a historical continuum that extends to our present as well as into the distant past.

Benjamin C. Tilghman specializes in the art of early medieval Europe, with particular interests in the symbolic aspects of ornament, the visual nature of writing, cross-cultural interchange in the North Sea basin, and phenomenological and object-oriented analyses of art. From 2007 to 2010, he served as a curatorial fellow at the Walters Art Museum, where he curated exhibitions on the Saint John’s Bible, miniature books, and Hubble Space Telescope imagery.

- 1. And was almost immediately cause for comment, as for example Karl Steel, “On the Staffordshire Hoard: A Rich Glowing Effect,” In the Middle, September 24, 2009, http://www.inthemedievalmiddle.com/2009/09/on-staffordshire-hoard-rich-glowing.html.

- 2. Catherine Hills, “The Primacy of Context,” Antiquity 85 (2011), 226–28.

- 3. For a good overview of the problems and possibilities, see Leslie Webster et al., “The Staffordshire (Ogley Hay) Hoard: Problems of Interpretation,” Antiquity 85 (2011), 221–29.

- 4. The idea that things “withdraw” from each other is a core component of recent work in object-oriented ontology, particularly that of Graham Harman. See, for example, The Quadruple Object (Washington: Zero Books, 2011), 35–50.

- 5. Translation from Craig Williamson, A Feast of Creatures (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1982), 141.

Figure 1. Sword fitting, England, mid-7th century, gold with cut garnets. Photo and digital enhancement © Daniel Buxton, 2009.