This article appeared in the Vol. 21 No. 1 / Spring-Summer 2014 issue of West 86th.

This article examines the development of a specific gendered discourse in the United States in the first half of the twentieth century that united key beliefs about feminine beauty, identity, and the domestic interior with particular electric lighting technologies and effects. Largely driven by the electrical industry’s marketing rhetoric, American women were encouraged to adopt electric lighting as a beauty aid and ally in a host of domestic tasks. Drawing evidence from a number of primary texts, including women’s magazines, lighting and electrical industry trade journals, manufacturer-generated marketing materials, and popular home decoration and beauty advice literature, this study shifts the focus away from lighting as a basic utility, demonstrating the ways in which modern electric illumination was culturally constructed as a desirable personal and environmental beautifier as well as a means of harmonizing the domestic interior.

Proper lighting can do much toward making or breaking a beauty reputation, yet many women ignore this factor completely.

—Arlene Dahl, 1961 1

In 1964 the American artist James Rosenquist painted F-111, an eighty-six-foot-long, twenty-three-panel exploration of American culture. Like a randomized montage of television imagery, Rosenquist’s fighter jet cuts across a larger-than-life landscape populated by wriggling spaghetti, a mushroom cloud and a rainbow-colored umbrella, a deep-sea diver’s exhalations bubbling up in the dark, a smiling young blonde girl sitting serenely under a hair dryer–cum–warhead, a sticky-sweet angel food cake, and the graphic chevrons of a Firestone tire. Employing the impossible juxtaposition of America’s exuberant consumerist lifestyle with the stark conditions of the nation’s involvement in the Vietnam War, Rosenquist critiqued American society with his own painterly act of war. In the center panel of F-111, the fighter jet’s bomb bay doors swing open to release three pastel-colored light bulbs upon this landscape of American popular culture. Why would Rosenquist choose candy-colored light bulbs to depict this act? In his biography he explains that the light bulb is a “metaphor for an egg; the idea of the fragility of the eggshell and the light bulb, which both burst when dropped like bombs.”2 An evocative metaphor to be sure, but it does not fully explain the use of pastel-colored light bulbs, which were introduced by all the major lamp manufacturers in the mid-1950s—a standard frosted incandescent bulb would have sufficed just as well. Perhaps on the most practical level the blue, yellow, and pink suited his brightly colored canvas better, but it is also possible that this trio of bulbs more succinctly expressed the contradictions inherent in the workings of American society. In the following study I would like to delve more deeply into the significance of the pastel bulbs, examining the historical trajectory of the development of these products and the relationship between their introduction and the cultural construction of gendered beliefs about feminine beauty, identity, and the domestic interior in the United States in the first half of the twentieth century.

The formative role of gendered cultural expectations in the everyday lives of American women from the mid-nineteenth century onward is hardly a subject of scholarly debate today. Numerous historical and theoretical investigations of the formations and agencies of womanhood, and manhood for that matter, in the United States have demonstrated the centrality of gender in the construction and negotiation of cultural meanings and material relations.3 For women, cultural expectations of gender often focused on domestic roles and responsibilities and notions of femininity. An established weft of the social fabric of American culture by the turn of the twentieth century, prescriptions regarding female behavior and appearance were tethered to such gendered beliefs. In this period women were inundated with domestic advice in newspaper columns, magazines, etiquette manuals, and advertisements about how to be better mothers, cooks, hostesses, housekeepers, decorators, and consumers. However, one subset of this advice literature that cut across spheres, private and public, young and old, single and married, was beauty. Like gender, feminine beauty was and is a social and cultural construction, long considered a primary constituent of female identity. In addition to hair dyes, powders, rouge, lipstick, and other cosmetic aids, electric lighting, the subject of this study, was among the many tools promoted for enhancing feminine beauty.

As a culturally constructed aspect of identity, beauty also implicated other related social beliefs and practices, including those constituting race and class. The intersection of dominant notions of race, class, and gender is apparent in the strategic development of the market for electricity in the first half of the twentieth century. In this period the electrical industry witnessed tremendous growth as utilities steadily built electrical load by focusing on increasing efficiency and scale of energy production.4 In order to increase demand equivalent to production improvements, the industry needed to diversify the nation’s electricity consumption. In addition to a raft of newly electrified domestic appliances introduced in the early decades of the twentieth century, residential electric lighting became a principal focus of the electrical industry’s colonization of the American market. Lighting manufacturers, typically working in partnership with electrical utilities, developed specialized marketing campaigns to sell lighting to residential customers. With lighting products developed to enhance Caucasian skin tones, residential lighting demonstrations in white-only housing developments, and marketing imagery representing white middle-class women, men, and families, the industry specifically engaged key signifiers of gender, race, and class grounded in the privileged position of white culture in pre–civil rights America. In this period particularly, whiteness both defined and embodied cultural norms in the United States. While the marketing of electric lighting was not overtly exclusionary of any particular race, it unquestionably reflected and represented a white middle-class ideal. In order to understand and destabilize the power of such a paradigm, Richard Dyer argues for the need to recognize “whiteness” as a racial condition. He describes how “whiteness” is perceived among white Western society as a “human condition” that “both defines normality and fully inhabits it.”5 The following study seeks to tease out key aspects of this inhabitation, acknowledging the role of whiteness as a backdrop against which notions of gender, race, and class were reconstituted within the American consumer marketplace in the promotion of electric lighting.

From the late 1920s onward the electrical industry’s marketing rhetoric relentlessly encouraged American women to adopt electric lighting as a beauty aid and domestic ally. With the assistance of a host of cultural authorities—from movie stars, to make-up artists, to beauty columnists—the industry promoted electric lighting as a powerful tool in the female arsenal, one able to “make or break” the impression of beauty. Across a range of popular literature, women were promised the glamorous advantages of Hollywood starlets if only they attended to their lighting. Alternatively, they were threatened with the fear of unflattering cosmetic effects and shameful embarrassment if careless with their lighting. Particularly in such associations, electric lighting was linked with that most elusive of qualities, glamour. As Alice Friedman argues in American Glamour, the meaning of this term grows out of “a web of shared references, narratives, and cultural values,” largely grounded in the visual language of Hollywood and the American fascination with charm and good looks.6 Historically correlated with mystery, illusion, enchantment, seduction, and irresistible attractiveness, glamour was well suited to both the cultural industry of Hollywood and the commercial interests of the United States’ burgeoning electrical industry. In his study of the mechanisms of Hollywood glamour in the 1930s, Stephen Gundle describes the translation of these strategies to the marketing of consumer products through promises of “instant transformation and entry into the realm of desire.” He argues that such commercial narratives of glamour were achieved by “adding colorful, desirable, and satisfying ideas and images to mundane products, enabling them to speak not merely to needs but to longings and dreams.”7 General Electric, Westinghouse, and Sylvania, America’s largest electrical manufacturers, led the industry in the early decades of the twentieth century with their efforts to build marketing strategies that positioned such notions of glamour and instant self-transformation within reach of female consumers.Drawing evidence from a number of primary texts, including women’s magazines, lighting and electrical industry trade journals, manufacturer-generated marketing materials, and popular home decoration and beauty advice literature, this study demonstrates how cultural beliefs about feminine beauty and domestic maintenance were correlated to appropriate lighting choices in the first half of the twentieth century. Shifting the focus away from lighting as a basic domestic utility, the industry positioned modern electric illumination as a desirable personal and environmental beautifier, as well as an emotional regulator. Although this dichotomy was rife in mass-media discourse, the evidence for the individual reception of such marketing strategies is scant, and it is not my intention to suggest that women accepted such messages with dronelike compliance.8 Rather, I offer a very narrow field of investigation, with the hope of providing some understanding of the ways in which the electrical industry sought to domesticate electric lighting and appeal to female consumers.

Color Harmony and Discord in the Domestic Interior

Surely each of you must know your own color-sense? … I have never believed that there is a woman so blind that she cannot tell good from bad effects, even though she may not be able to tell why one room is good and another is bad. It is as simple as the problem of the well-gowned woman and the dowdy one.

—Elsie de Wolfe, 19139

Concerns about color distortions caused by artificial light long predated the introduction of electric light, and indeed were common with the widespread use of gas and kerosene lamps in the nineteenth century. Etiquette manuals and home decoration journals described muddied colors and sickly complexions produced when personal attire and interior furnishings were not coordinated in relation to the effects of artificial light. Such warnings were typically included within more general advice for women concerning color-palette selection. Hill’s Manual of Social and Business Forms of 1888 details the appropriate colors to be worn by the principal “complexion types” of white women. Describing the colors suitable to each type, Hill offered a detailed account of possible flattering and harmonious color combinations. For example, he suggested, “Dark violet, intermixed with lilac and blue, give additional charms to the fair-haired, ruddy blonde…With the very ruddy, the blue and green should be darker rather than lighter. An intermixture of white may likewise go with these colors.” After setting forth the most suitable colors for each complexion type, Hill described which are best after dark, cautioning readers that while a dress of a given color “may be beautiful by the day,” under the illumination of gaslight at night it “may be lacking in beauty.” Pale yellow, he wrote, is “handsome by day” but “is muddy in appearance by gaslight.” Similarly he suggested that “the beauty of rose-color disappears under the gaslight; and all shades of purple and lilac, the dark-blues and green, lose their brilliancy in artificial light.”10

Expanding upon such advice, A. Ashmun Kelly wrote for The Decorator and Furnisher in 1895 about the difficulties stemming from artificial lighting, giving particular attention to the domestic interior and the women within it. Referencing common knowledge of the issue, Kelly suggested that “interior decorations and furnishings, and likewise the clothing and complexions of persons are, as it is well known, greatly modified in color by having artificial light, especially that from gas or kerosene, to fall upon them. Sometimes, and indeed very often, these effects prove quite serious matters, changing entire aspects of rooms, and giving a very undesirable and displeasing hue to the skin.”11 Kelly proposed that such conditions could be avoided, or if already existing, that they could be “greatly modified, or even removed altogether.” All that was needed to remedy the situation, he argued, was “knowledge of the laws governing color and its source—daylight.”

As Kelly analyzed the many potential color combinations for individual complexion types and interior palettes in relation to the effects of artificial lighting, it became apparent that this was no simple matter. Rather, Kelly’s approach required a sophisticated understanding of the “principles of colors, their combinations, proportions, tints, shades, and hues” in order to “properly estimate the varied harmony or discordant effects upon each other when placed in juxtaposition.” However, the new technology of electric light promised to simplify such calculations because of its similarities with sunlight in “appearance and effect,” which, as Kelly noted, greatly minimized color distortions.12

No doubt related to the complicated nature of creating and maintaining personal color harmonies, popular literature addressing the domestic environment and feminine beauty in the late nineteenth century frequently featured advice organized around “types” representing the spectrum of white women’s complexion combinations. The classification of female complexion types was not limited strictly to hair, eye, and skin color but also frequently included aspects of personal character as well.13 The expression of one’s “inner character” in the selection of an appropriate color palette was a common subject in beauty advice literature throughout the period, and from the late nineteenth century onward, artificial lighting also joined the discourse on color coordination, dress, beauty, and interior decoration.

Flattering Complexions

Getting the right color of rouge is but half the trick of a clever makeup. The other and bigger half is putting it on under the right light.

—Antoinette Donnelly, 192614

As if the daily task of composing oneself following such perplexing guidelines was not difficult enough, in the early twentieth century an additional consideration was added to the mix: make-up. Unlike the more laborious process of defining an appropriate personal color palette or developing decorative strategies to better harmonize with one’s physical surroundings, cosmetics offered the potential for immediate and dramatic transformation—a key characteristic of glamour. In the nineteenth century the discourse on feminine beauty emphasized the importance of revealing moral and spiritual character through one’s “natural” complexion, which could be enhanced with an array of “moral cosmetics”—such as soap, lotions, exercise, and temperance.15 By the turn of the century, however, the use of visible, masking, and colored cosmetics became more common, particularly among women holding public positions, where it was seen as an aid in performing certain roles. Stage actresses, with their reputations as popular icons known for their beauty and glamour, were employed in the promotion of cosmetics, often in the form of advertising testimonials.16

Similarly, the increasing popularity of photographic portraiture, where corrective cosmetics were commonly used to present a more composed facade to the camera, also contributed to the legitimization of make-up as a beauty aid. Together the public display and popular endorsements of cosmetics paved the way for new cultural expectations of female beauty, which encouraged artifice as a means of enhancing the “natural” self. As the use of cosmetics became more broadly acceptable for American women in the first two decades of the twentieth century, advice manuals and beauty columnists began to distinguish between the use of make-up for daytime versus nighttime activities, advising the use of face powder and rouge in environments characterized by “artificial light, spectacle, and pleasures.”17 Make-up manufacturers targeted middle-class American women, promoting cosmetics as a means of “achieving upward mobility and personal popularity” within the public arena—including the workplace, boardwalk, theater, and other artificially illuminated environments. Such spaces of public spectacle provided women with new opportunities to enact modern identities. Electric light, with its dazzling, transformative properties, provided a context that encouraged, and perhaps even legitimized, the increasingly performative nature of American femininity in the early decades of the twentieth century.18

The effects of artificial light on the appearance of applied cosmetics, particularly colored rouge and lipstick, became a common subject of popular beauty advice from the 1920s onward.19 Frequently electric lighting was blamed for cosmetic faux pas. Syndicated columnist Antoinette Donnelly, who wrote for the New York Daily News from 1919 until 1963, often incorporated specific details about lighting in her beauty advice to readers.20 In the nineteenth century concern had focused on flame-based illuminates and the potential for airborne fumes produced by the burning gas to oxidize the compounds used in white women’s cosmetics, thereby turning pale pink powders into muddy, opaque browns. This was an environmental problem rather than one of personal judgment and attention to detail. With the popularization of electric lighting, however, the principal danger was of incorrectly applying cosmetics by not taking into account its effects. A woman risked being exposed with embarrassingly unbalanced make-up if she applied her cosmetics under the wrong light. As Donnelly described, “the dangerous possibility nowadays appears to be not from fumes, but from use of electric light when making up for the street. In crowded centers it is rather the exceptional woman who uses daylight when she applies makeup for daylight wear. It is due to the electric light then that we see so many instances of poorly applied rouge.” Similarly she instructed readers on preparing for inverse conditions: “No more can you consider the day makeup for night wear.”21

Thus, by the end of the 1920s a woman was expected to apply her cosmetics with close consideration to the type of light in which she would be seen. With this knowledge in hand, she could compose her make-up to best enhance her complexion and attire, and be confident that these colors would not distort or mutate during the course of her activities. As Donnelly reminded her readers in 1932,

Get your dressing table, then, over near the window so the bright light falls directly on your makeup work. Or, if your appearance is to be made at an evening function, get the benefit of clear electric lighting on it. This may seem a small detail, but it is not. Personally, I think it is the reason one sees as many poorly matched complexions and badly applied makeup as one does. Heaven knows it isn’t that women are not anxious to create the best of effects.22

Marketing from the period leveraged such arguments. A General Electric advertisement appearing in Better Homes and Gardens in 1931 inquired of its readers: “Can you light your bedroom correctly?” (fig. 1).23 The text of the advertisement suggested that good lighting, such as that produced by Edison Mazda lamps, would not only “add to the pleasure of preparing your toilet” but also protect against the “grotesque coloring of lips and cheeks” resulting from poor lighting at vanity mirrors.

Indeed, the dressing table and vanity mirror served as pivotal objects in advice literature addressing the role of daylight and electric illumination in daily feminine grooming. In the 1920s women’s magazines and newspaper columns frequently featured items regarding the design and use of the dressing table. Electric lighting and adjustable mirrors to see oneself from every angle were described as necessary for daily beauty inspections. In 1924 Vogue magazine described the advantages of the modern dressing table: “its many mirrors and its lighting tell the whole truth about the woman before it with an honesty that is an inevitable spur to wise vanity.”24 Similarly, Donnelly reprimanded women who insisted on applying their make-up in “corners of rooms where good light is hampered by taffeta curtains or chintz.” She then directed them—after getting the light right—to peer closely and identify their complexion type. It was imperative to have a clear understanding of one’s skin coloring, according to the beauty columnist, in order to make the right make-up choices. Donnelly warned against the temptation to allow insecurities and personal preferences to influence the evaluation of one’s complexion. She argued that women were often unable to clearly assess the most flattering make-up choices because of a tendency toward “color complexes” and sentimental decision making.25 To avoid such weaknesses, Donnelly advised seeking a friend’s assistance to identify the most becoming colors. The suggestion to rely on the vision of a friend underscores the importance in much of the beauty discourse of the period of presenting oneself appropriately in a social context and of being aware of how one looked to others.

Personality and the Construction of Feminine Identity

Stand before a mirror and study your face, your personality. Then put on make-up and see if it harmonizes with your mental and physical self. Paint yourself as you would have nature paint you.

—Max Factor, 192926

Along with the growing focus on make-up in the popular discourse on feminine beauty and women’s social roles during the first three decades of the twentieth century came the triumph of “personality” over “character” as the primary mode of self-expression. While some have argued this is representative of a larger shift in the United States from the prominence of character as the basis of a moral and sound society in nineteenth-century discourse to the secular and individualistic identification with personality in the twentieth century, it is beyond the aims of the study at hand to critique this body of literature.27 However, without question in the first decades of the twentieth century, popular culture increasingly celebrated well-known, media-crafted personalities from theater and Hollywood as paragons of female beauty. Historian of Hollywood’s star culture Sarah Berry has argued for the emergence of a new “democratic” concept of beauty associated with the rise of personality. She suggests it was predicated upon the logic of a consumer economy, particularly in its proposition that every woman could be beautiful with “good grooming and makeup.” Berry proposes that beauty held a recognized value for women within the nation’s growing service economy, and as such was commonly understood as a legitimate form of social capital. She writes, “Women’s cosmetic self-maintenance came to be seen as one of the requirements of feminine social values, rather than an unethical preoccupation with personal vanity.”2828 The cultivation of the right “look” was equated with the ability to make the right “impression,” get the right job, or capture the attention of the right man. Although personal beauty had long been a means for women to access social acceptance, popularity, and admiration, in the twentieth century increasing emphasis was placed on a woman’s ability to invent, transform, and control her appearance through a host of beauty aids, including electric lighting.

Such notions underscore the articulation of codes of feminine beauty in the United States from the 1920s onward. Max Factor, a leading make-up artist during Hollywood’s golden age and a founding figure in the modern cosmetics industry, pronounced in an interview from 1929,

Beauty is more than skin deep when observed by the onlooker. It is everything. It creates the first impression. It may be the key to happiness and success, the open door through which a girl finds access to those things most desired. Nature’s work is often incomplete. Beauty is naturalness—idealized.29

Personality was the foundation of this naturalness for Max Factor. He instructed women to look long in the mirror, studying the face to determine the exact personality belonging to the reflected image. He said, “There is a mental, guiding psychology about the decoration of one’s face. The girl who is sprightly, vivacious, colorful in personality and disposition may wear a more colorful make-up and not have it appear unnatural. But there is the more siren-like, the more languorous type of beauty who must resort to more subdued tones.”30 Here Factor correlated appropriate make-up choices not with a woman’s complexion type, as was typical previously, but rather with her personality.

There was an additional benefit for the cosmetics industry in shifting emphasis to personality—unlike character or complexion, personality could be altered or exchanged easily through make-up color selection and coordination. Personality, as a fluid form of identity, could be determined by the individual woman to suit her immediate mood or objectives.31 Such attitudes were promoted in Hollywood fan literature and popular beauty advice throughout the 1920s and 1930s. An article appearing in the Chicago Tribune in 1935, titled “Makeup Expert Able to Paint Personality on Faces,” detailed the techniques used by the film industry’s make-up artists and cinematographers to create different personalities for popular stars of the era. Offering women step-by-step instructions, the make-up artist Pere Westmore claimed, “It is really possible to paint a personality on a face, using the face as a canvas.”32 With even greater emphasis on the adaptable nature of personality, the Hollywood starlet Joan Blondell advised readers of the fan magazine Photoplay in 1939, “The whole secret of beauty is change…A girl who neglects changing her personality gets stale mentally as well as physically. So I’m going to vary my hair style, my type of make-up, nail-polish, perfume.”33

Such accounts of the performance of feminine identity were common in the United States leading up to World War II. New York Times beauty columnist Martha Parker wrote in 1943 of a range of facial “lighting effects” possible with a new cosmetic powder that would allow a woman “to change her skin tone to the color of her costume almost as easily as an electrician switches a stage set from rose to gold.” The analogy with stage lighting was hardly accidental. Drawing connections with theater and film stars and offering the promise of similarly dramatic beauty effects was a common strategy. According to Parker, the new powder also would allow any woman to “wear any dress shade at all, becomingly.”34 However, the pastel powder products Parker describes clearly were not appropriate for all women. African American women and others with darker-toned skin also sought the transformative potential of cosmetics, however. As Kathy Peiss has argued, “African-American beauty culturists made cosmetics central to the ideal of the ‘New Negro Woman.’ As consumers of beauty products, they argued, Black women could change the stereotyped representations that socially and sexually debased them.”35 The incredible attraction of the promise of transformation, of the ability to reconfigure one’s identity, one’s physical appearance, and one’s social station, transcended boundaries of race and class in the United States. As Sarah Berry has argued, “Just like Hollywood’s ingénues and sirens, the cultural role models for American beauty were Caucasian with hardly an exception in this period. Yet, in the popular press, such self-transformations actualized through new lipstick hues, facial powders, or other cosmetic fashions were associated with a seemingly democratic opportunity for personal pleasure and empowerment, particularly, with the ‘pleasure of potentiality.’”36

Personality and the Domestic Interior

A dwelling should be suggestive of home. Moreover, the house which is to be your home—in short, your background—should unmistakably suggest you. Its personality should express your personality.

— Emily Post, 193037

The emphasis on personality that emerged in beauty advice literature in the late 1920s and 1930s similarly became a primary theme of home decoration advice during this period. Emily Post, a prominent twentieth-century source on the application of a spatialized concept of personality to the domestic environment, helped popularize the term among the American public, first in her 1922 publication Etiquette and later with The Personality of a House in 1930.38 Post’s concept of personality was a refinement of gendered nineteenth-century notions linking the appearance and psychological spirit of the interior with the character of the female head of household.39 Historian Beverly Gordon has called attention to this gendered symbiosis, citing Harriet Beecher Stowe, in We and Our Neighbors (1875), who suggested: “[Her] self begins to melt away into something higher…The home becomes [her] center and to her home passes the charm that once was thrown around her person…Her home is the new impersonation of herself.”40 In Post’s twentieth-century reinterpretation of this relationship she suggested that while the personality of a house was largely “indefinable,” it could be appreciated through the psychic experience of the domestic interior. She likened this indefinite quality to “charm.”41 The domestic environment was to be understood as a personalized “backdrop” for daily life, and as such, it should embody and express the woman it framed. Describing the lifelessness of a house that did not meet this basic requirement, Post wrote, “The house that does not express the individuality of its owner is like a dress shown on a wax figure. It may be a beautiful dress—may be a beautiful house—but neither is animated by a living personality.”42 A prime component of domestic personality according to Post was charm, which she described as synthesis of “beauty, taste, sympathy, appealing manner, and so forth.”43 Outlining the ways in which a woman could create a charming and enchanting interior, one that embodied or at the very least harmonized with her personality, Post ranked color as a primary consideration.44 Post was not alone in her estimation of color’s importance; from the 1920s onward color was broadly considered a primary mode through which to express or modify one’s personality.

Because of the importance of color in the articulation of personality and charm in the domestic interior, simplified guidelines about how best to approach color-palette selection and coordination became a core concern of interior-decoration advice literature targeting female readership. As with the discourse on make-up, artificial lighting figured prominently as a common and challenging factor influencing color selection for the interior. Vogue magazine advised its readers in 1925 that “‘light is the first of the painters,’ and no room can be attractive unless it is adequately and charmingly lighted.”45 The article suggested that “the failure of many a dinner party” could be attributed to glaring and thoughtless lighting. Calling upon Elsie de Wolfe, one of the founding figures of modern interior design and a celebrity in her own right, Vogue advised readers about the “perfect lighting of livable rooms.”46 Arguing that lighting arrangements must be carefully considered, de Wolfe proposed that with “proper lighting, the harmony of the home is increased.”47 One of the more significant challenges to fostering harmonious lighting in the home, according to de Wolfe and others, was the introduction and popularization of colored lampshades for electric lights. The use of colored lampshades was widely criticized because of the difficulty presented in predicting and coordinating the effects of the light produced by tinted shades. A 1927 column appearing in the women’s pages of the Atlanta Constitution suggested that “the colors of lamp shades should be of even greater consideration to the homemaker than any other colors in her home decoration scheme, because lighted colors comport themselves differently from the way they do when unlighted, and to use color satisfactorily it is important to understand them. This fact should be known before incorporating them into the home color scheme.”48

Likewise, in 1925 Vogue magazine featured an article by the well-known English interior decorator and tastemaker Syrie Maugham on the selection of light fixtures and shades for large rooms. Maugham advised readers, “Lighting a large room where people receive is a decorative problem that always requires much consideration.”49 Describing a variety of potential social uses for such spaces, Maugham suggested, “In arranging the lighting of a drawing-room, there are many things to remember. First, there is attention to the colour scheme of the room. Lights can kill colour, or give it rebirth.” To avoid the untimely death of one’s color palette, Maugham instructed that “strong colours for any lighting fixtures entirely destroy the fixed personality of a room.” In conclusion, Maugham reminded readers that it was the hostess’s responsibility to provide flattering conditions for her guests: “For the guest who brings her vanity—and most guests do—there should be two or three chairs bathed in a mellow radiance that is displaying and becoming.”50

The notion that a woman was responsible for creating an environment where both she and her guests would appear at their most attractive was common in advice literature throughout the first half of the twentieth century. While some authorities like Maugham advocated for the complete avoidance of colored light (not surprising given her fame for pale, monochromatic interiors), others suggested that the careful use of colored light could enhance the beauty of the interior, the guests, and the woman herself. Women’s clubs reporter Myra Nye reported in the Los Angeles Times in 1932 on a demonstration of new electric lighting techniques given by George M. Rankin, director of lighting for the Southern California Edison Company.51 In the demonstration Rankin illustrated how colored lights were utilized in retail window displays to “enhance the richness of drapes and gowns.” Rankin advised his audience that these same techniques could be equally effective in the domestic environment. Using a wax figure Rankin illustrated how various combinations of colored light could “change the color of the hair and complexion, as well as the contours of a person’s face.”52 Such promising lighting applications for the domestic environment and personal beauty were largely put on hold during World War II. Wartime restrictions and the disruption of domestic life and routines in the United States shifted popular discourse away from such concerns, with greater focus given to personal restraint and contribution to the war effort. However, consideration of color and electric light as a means of manipulating the experience of the domestic interior was far from neglected during the war. When the United States instituted blackouts as a defensive (and symbolic) measure, color and light were enlisted to maintain “cheer” within the nation’s homes. The Washington Post reported in 1941 that mandated blackouts did not “mean that homes will be without cheer.”53 Rather, the Post argued that maintaining the quality of “home sweet home” was more important than ever during blackouts and urged readers to use color and electric light to “maintain civilian morale.” In the article, Post household editor Martha Ellyn consulted with the American decorator Bertha Schaefer, who described the value of color and lighting in maintaining a harmonious and peaceful domestic scene: “Too few homemakers realize that the lighting of the home may be a strong factor in soothing irritations, and in keeping a balance between conflicting personalities. By that I mean creating a setting of unfailing harmony and peace. And I feel that just now such effort may be a real morale builder.” While the article primarily addressed maintaining civilian spirits and standards within the home, the focus on personality, color, and lighting was consistent with the prewar period. As the war came to a close and American society returned to its consumer-centrism, the electrical industry developed a raft of new lighting products and applications geared for greatest appeal to women consumers.

Lighting, a “Background for Living”

We are no longer just selling light bulbs; we are selling luminous environment.

— General Electric, 195654

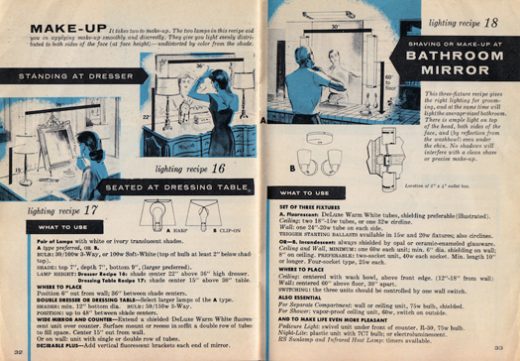

In the mid-1940s, with the end of World War II on the horizon, American industry shifted its focus from war production to the development and expansion of the consumer goods market. Prior to the war’s end, leading manufacturers recognized the importance of achieving a successful postwar reconversion through the cultivation of a thriving consumer economy.55 A principal area of focus in the nation’s economic recovery was investment in new home construction and the endorsement of consumer credit. Driven by widespread housing shortages and the financial incentives of Veterans Administration benefits and the Federal Housing Administration’s support of the mortgage market, new home construction skyrocketed after the war. Within two decades of the war’s end approximately 60 percent of Americans owned their own homes, as compared with only 44 percent in 1940.56 With the influx of unemployed soldiers, many middle-class women returned to domestic duties after the war, while labor shortages in nursing, teaching, social work, and white-collar industries alternatively drew women to work in these fields. As historians Joanne Meyerowitz, Susan Hartmann, and others have demonstrated, the popular notion of the 1950s domesticized housewife is a simplified cultural construction that obscures the diversity of experiences for women in the postwar period.57 Whether as the female heads of households or as wage earners, women had tremendous agency as consumers, contributing to the nation’s economic recovery through consumer spending.58 Indeed, raising and maintaining the standard of living in the United States was central to the nation’s strategy for seeding postwar prosperity. Across government, industry, business, labor organizations, and popular media the overriding message in the postwar era was that “mass consumption was not a personal indulgence, but rather a civic responsibility designed to provide…improved living standards for the rest of the nation,” as Lizabeth Cohen has argued.59

With residential construction and consumer spending as principal areas of economic growth in the postwar period, government and industry alike sharpened their focus on the domestic market as a key agent in the prosperity cycle, favoring narratives of domesticity and family life. A striking advertisement that ran in 1943 for Sylvania lighting products featured a woman dressed in workers’ clothing, standing on the factory floor, looking thoughtfully, even maternally, at an industrial fixture in her hands (fig. 2).

Just below is a smaller, inset image of the same woman in feminine day wear standing in a homey kitchen holding a domestic Sylvania fluorescent fixture steadily in her hands and gaze. The text reads, “Note to homeowners: This means something to you, too. It foretells the day—not now, but after Victory—when you will have efficient fluorescent lighting in your own home.”60 While the emphasis in such wartime advertisements was on improved efficiency and lighting levels, in the postwar period, industry marketers increased the emphasis on the gendered enticements of beauty, charm, and personality.

The rapid development of the domestic consumer market by leading electrical manufacturers was direct and purposeful in the decade following the end of the war.61 The competitive pressure on even the biggest of American companies to establish and maintain market share was significant, as General Electric’s president, Charles E. Wilson, candidly described in 1947 for the Wall Street Journal: “We’re not kidding ourselves. The fight for business in the period ahead will be more rugged than anything we’ve been in up to now.” He further suggested that the company’s production of consumer items would be greatly expanded in order to “bring into balance for the first time G.E.’s consumer and industrial business.”62 In the hopes of gaining advantage in the booming postwar consumer goods market, companies like Westinghouse, Sylvania, and G.E. focused on the American way of life, positioning modern lighting as an essential condition of modern living.

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s the major electrical manufacturers by and large had employed some variation of the “Better Light–Better Sight” marketing campaign, which promised improved sight for daily tasks and therefore increased efficiency through higher light levels.63 In the postwar period emphasis was shifted instead to the lifestyle benefits made possible through a diversity of lighting applications. As Barron’s reported in 1958, looking back over changes in the lighting industry in the preceding decade, “Good lighting, the company [G.E.] has discovered, can be sold as an adjunct to interior decoration far more readily than as a sight-saver. Hence it has launched a ‘Light for Living’ campaign, which places heavy emphasis on the use of light to ‘glamorize’ the home.”64

Such messages were quickly absorbed and disseminated through popular media. Mary Roche, New York Times home editor, reported in 1945, “If there is any one invention that promises to make our homes of tomorrow radically different from our homes of yesterday that one is modern lighting.”65 While “most people are likely to think of better light as more light—for reading, for darning socks, for getting a better look in the mirror,” Roche posited that it was the overall quality of light, rather than quantity, that made the modern interior attractive. The best kind of light, she argued, is indirect light, or light that is diffused over a large area to provide shadowless illumination. However, this alone was still not sufficient, as Roche explained: “A room with nothing but indirect lighting would look as flat as an anemic blonde with no make-up. So the lighting designer has to balance local lighting with general, direct with indirect, in a way that will enhance the room and its contents, highlight the lines of furniture, accent the colors.”66 While it may simply be coincidental that Roche likened the poorly lit room to a woman without make-up, it nevertheless suggests the persistent correlation between women and the domestic environment, cosmetics and beauty, personality and lighting.

Immediately following the end of the war the lighting industry lobbied female consumers to integrate a variety of electric illumination applications into their interior decor. Among the more prominent vehicles for the dissemination of the electrical industry’s rhetoric were popular home and garden columns in the nation’s leading newspapers, residential lighting demonstrations, model home installations, and nationally distributed lighting “recipe” booklets. Roche’s article is a perfect example. In addition to prophesying the transformative power of light for the “home of tomorrow,” in this single column Roche also included descriptions of new lighting applications employed in Westinghouse and John Wanamaker’s model “Home of Vision” in Philadelphia, the Illuminating Engineering Society’s new residential lighting manual, and General Electric’s booklet Light for Living.67 Across the spectrum of popular media the industry’s message for women was consistent—electric lighting was the new conduit for modern living. In 1947 Illuminating Engineering noted that “books on home decoration…are showing an interesting trend toward greater attention to the lighting of a room and its relation to the decoration.”68 The article cited a host of new publications featuring or focused on the lighting of domestic interiors, including four decorating manuals each with a chapter devoted solely to illumination in the home, one book that had two chapters, and an additional book that treated lighting in every chapter. Illuminating Engineering also reported that 1947 marked the Encyclopedia Britannica’s first inclusion of a full-page plate on artificial lighting, with material provided by Myrtle Fahsbender, chairman of the Illuminating Engineering Society’s Committee on Residence Lighting.69

Fahsbender, a key figure in several residential lighting programs and one of a number of prominent women working as lighting consultants for the electrical industry, urged women to educate themselves as lighting specialists. Beyond growing their female customer base, the industry cultivated and supported a number of female residential lighting specialists, including Fahsbender and Priscilla Presbrey at Westinghouse, Aileen Page at General Electric, Jan Reynolds at Sylvania, and Mary Dodds at the Toledo Edison Company.70 Fahsbender began her career in 1929 as a secretary for the Chicago Lighting Institute, but she quickly advanced through the organization to serve as a home lighting consultant. She then joined the Westinghouse lamp division in 1936 and became a media spokeswoman for residential lighting—giving lectures across the country, writing numerous articles for magazines and trade publications, and contributing to educational booklets, as well as working on new fixture designs and lighting applications.71 In an interview with the Christian Science Monitor in 1946, Fahsbender claimed, “Because of women’s natural preoccupation with the home…they are especially qualified to become lighting consultants.” Not only were women inherently prepared for the task, she argued, but they also had every reason to take up this cause: “For years, people have built beautiful homes, carefully selecting just the right furnishing and accessories to harmonize…but none of these things can be fully appreciated at night. When the lights are turned on, because the lighting has not been planned as part of the decorative scheme, much of the loveliness is lost.”72 In this article and many others like it, women were reminded of the potentially disastrous aesthetic effects of inadequate or inappropriate electric lighting. What was at stake was the loss or at the very least the obscuring of beauty, charm, and domestic harmony. Yet the threat never came without the solution: repeatedly, integrated (and extensive) electric lighting was promised as a means to unmatched interior beautification—enriching colors, unifying furniture groupings, ensuring emotional stability among family members, and renewing the charm and beauty of the woman and her domestic backdrop.

Day and Night, Ladies, Watch Your Light

What makes nature beautiful? It is light—sunlight, moonlight, and artificial light . . . The same is true of the human face. The light that illuminates it is most important.

—John Alton, 194973

While domestic maintenance formed one theme within the marketing of electric lighting in the postwar period, increasing emphasis was given to its overall glamorizing potential. References to both the instant transformation available at the flick of a switch and the cinematic adaptability of modern lighting techniques and technologies reiterated the connection between electric illumination and glamour. As had been the tradition since at least the 1930s, Hollywood’s starlets and artists were called upon as authorities on the cultivation of beauty, charm, and personality. In 1951 the Chicago Daily Tribune featured an interview by actress and beauty columnist Arlene Dahl with MGM cinematographer John Alton addressing lighting as a beauty aid. Alton began with a familiar warning, lamenting, “Women worry me…They go to all sorts of trouble dressing and putting on make-up, then ruin the whole effect with bad lighting.”74 Likely informed by the many hours he had spent behind the camera, Alton stressed the importance of proper illumination in controlling one’s own appearance, as well as its role in mediating the performance of feminine beauty. He insisted, “It’s too bad women today don’t realize that light can be a great factor in personal beauty. Too often we think of it merely in connection with seeing, not with being seen.”

Focusing his advice first on the bedroom, Alton referenced his contribution to the recent popular film An American in Paris (1951), provocatively describing how a woman could achieve a similarly luminous effect to that used in the climax of the romantic ballet scene with Gene Kelly and Leslie Caron. To create this type of soft, rosy lighting in the “boudoir,” Alton suggested women use translucent pink or peach lampshades. With close attention to possible motivations in lighting the bedroom, Alton recommended that if a woman preferred to “emphasize the beauty of her figure rather than her face,” she should use indirect wall lighting in order to “be silhouetted as she moves about the room.”75 Rather than offering specific lighting techniques to make interiors more attractive, Alton challenged women to light their interiors as if they were scenes in a Hollywood film, manipulating the lighting to create the mood they desired (in the bedroom no less!) and to best accentuate their particular beauty assets.

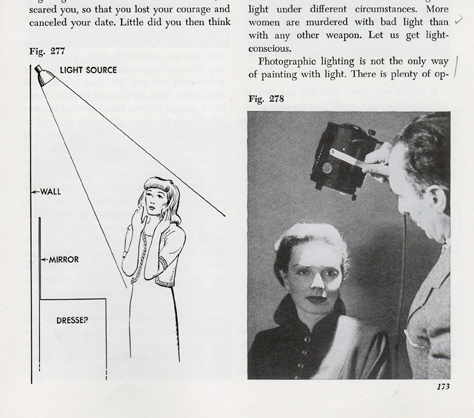

Alton’s interview with Dahl was framed as a promotion for his book, Painting with Light, published in 1949, but it is more likely that it was driven by industry influence. It is unusual for a book to be actively promoted two years after its publication; however, 1951 marked the second year of General Electric’s “Light-Conditioning” program and the company’s new focus on selling updated lighting for existing homes rather than new ones.76 Alton’s book, ostensibly a handbook for amateur photographers describing the basic techniques of photographic lighting common in Hollywood cinematography, also included a chapter specifically written for women titled “Day and Night, Ladies, Watch Your Light.”77 This unique chapter offered women tips on how to utilize electric lighting to their best advantage as well as cautionary tales describing what would happen if they did not.78 Alton argued that most women were oblivious to the aesthetic benefits of proper illumination, and he warned that in many cases women allowed their beauty to be ruined by “murderous illumination.” Even more dramatically, he argued that in such conditions a woman might be “slowly illumurdered” (fig. 3).79

Although enthusiastic about recent developments in “home illumination for decorative purposes, for beauty of the home,” he complained that far too little had been done “to beautilluminate the individual.”80 One of the key aspects of Alton’s perplexing neologism “beautillumination” was “glamorlight,” which he described as very gentle indirect illumination: “almost no light; it is soft, and no matter where it comes from, will do the face no harm.”81 Throughout the chapter Alton addressed women in the first person, repeatedly suggesting that personal beauty was possible for any and every woman, if only the right combination of lighting techniques were employed. Making the connection between beauty and personal and professional success, he argued that proper illumination would “open doors of opportunity—whether it is for a desired job or man.” According to Alton, “Love at first sight is love at first light.” Promising the glamour and magic of Hollywood, Alton advised, “Whenever possible, see to it that you are in the right light, and look your best. By properly distributing lights in your home, surrounded by well-lighted happy people, you can make it a pleasant place in which to live.”82 In so doing, Alton linked a woman’s personal beauty and a beautified domestic environment with self-realization.

A Light Bulb That Flatters

Fixtures and lamps should not only increase visibility but also create mood and atmosphere, adding to the pleasure and satisfaction in homemaking. With proper lighting, rooms seem larger, colors appear richer, and furnishings—yes, and people—look more attractive.

—Los Angeles Times, 195783

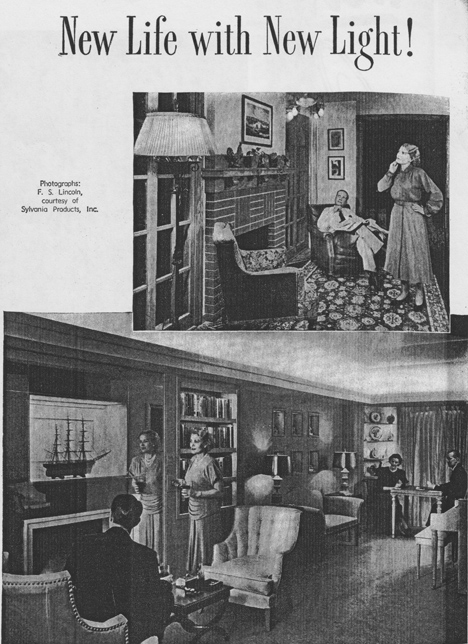

One of the more commonly cited problems in selling modern lighting to postwar consumers was the complexity of applications and the many elements necessary to realize a complete interior illumination scheme. While it was a straightforward marketing task to sell electric washing machines, dryers, dishwashers, and other domestic appliances, electric lighting was a complicated system of parts that could not be so easily wrapped up and sold as a self-contained unit. This problem was amplified further with the popular acceptance of indirect lighting as the most flattering backdrop for modern living. Indirect lighting required the integration of lighting fixtures into architectural features or the use of other masking or reflecting devices. Additionally, such background lighting, however pleasant, did not obviate the use of localized task and accent lighting. Beyond these considerations, there also remained the issue of control systems, including dimmers and switches. For example, a typical feature appearing in The American Home in 1949 entitled “New Life with New Light!” encouraged readers to transform their living spaces and lifestyle with modern electric lighting. The article suggested such improvements as recessed lighting in bookshelves, accent lighting for the china display cabinet, niche lighting for a “shadow box” above the fireplace (adjustable with dimmers), and recessed cove lighting along the cornice of the room (fig. 4). Certainly this must have been a daunting challenge for typical homeowners with limited knowledge of the standards and requirements of such lighting installations.

The challenge of simplifying residential electric lighting solutions continued well into the 1950s. As the Washington Post reported in 1956, “It is obviously impossible to arrive at a single lighting formula that can be applied to all situations.”84 With the hope of minimizing some of this complexity, lighting manufacturers and regional utility providers collaborated on a variety of educational marketing campaigns offering consumers guidelines for lighting specific tasks and room types. Among the industry’s more successful strategies was the hosting of “light conditioning” parties, mimicking the direct-sales approach innovated by Brownie Wise for Tupperware in the early 1950s.85 In this program, selected homemakers worked with residential lighting consultants, furnished by local utilities and sponsored by General Electric, to modernize their illumination plan. Then they would invite their friends and neighbors over to experience their newly light-conditioned homes. Unlike other direct-sales strategies by which many women earned incomes, however, there is no evidence that the women participating in the light-conditioning parties received any financial reward for their efforts. The incentive for their participation would seem to have been the enjoyment of updated domestic lighting provided by the program. Barron’s reported in 1956 on the success of the program, telling the story of a Mrs. Hightower from Jackson, Mississippi, who hosted a light-conditioning party: “On the spot, ten of the 15 women present decided to light condition their homes, too, to the pleasure and profit of everyone from the electrical manufacturer to the local public utility. While Mrs. Hightower perhaps was not aware of it, she and hundreds of other housewives who have given such lighting parties during the past year are key figures in a growing campaign designed to quadruple residential sales of light bulbs and fixtures in the next decade.”86

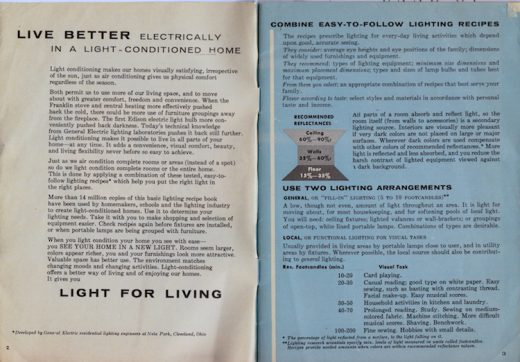

Such programs were organized to suggest a limited range of solutions to the most common residential lighting challenges and were broadly promoted under the Light for Living marketing campaign, introduced by General Electric in late 1950. The company spearheaded the development of specific residential illumination guidelines and presented them as “recipes,” invoking more familiar domestic tasks and naturalizing the technology of electric light and its integration into daily life.87 For example, General Electric’s thirty-eight-page booklet See Your Home in a New Light had been distributed to more than fourteen million readers by 1955 and included recommended reflectances for ceilings, walls, and floors, as well as suggestions for appropriate footcandle ranges for a variety of daily tasks. It also offered an overview of numerous possible fixtures, diffusers, bulb types, and more, as well as a host of other task-specific guidelines (figs. 5, 6).88 Yet despite obvious efforts to reduce confusion, these booklets generalized prescriptions more than they simplified domestic lighting.

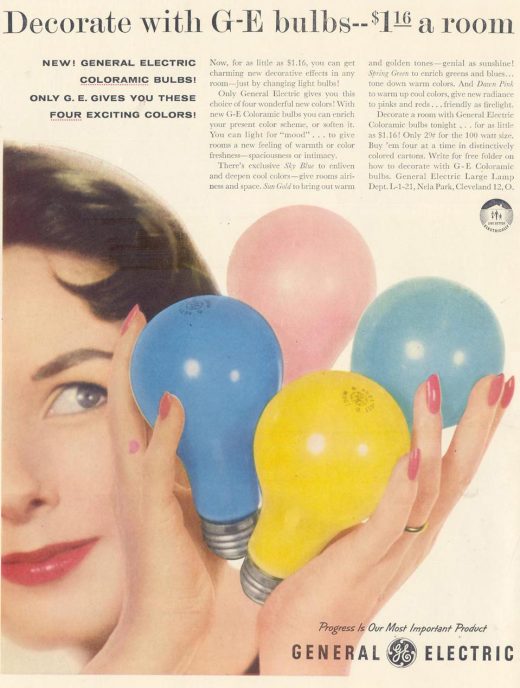

In 1955, however, the industry turned a corner, with each major lamp manufacturer almost simultaneously introducing a singular product that promised a range of residential lighting solutions. These “miraculous” products—pastel ceramic-coated incandescent light bulbs—were designed specifically for female consumers and were marketed with heavy emphasis on their beautifying and glamorizing effects. Arlene Dahl hinted at the benefits of the new products for women in her syndicated column “Let’s Be Beautiful” in 1955.89 Somewhat breathlessly, she described the flattering effects of a new pink-toned light bulb: “It’s amazing how your complexion—and indeed your whole room—gets a beauty boost when you use these bulbs instead of ordinary white ones.”90

The new pastel-colored incandescent bulbs, about which Dahl expressed such enthusiasm, enabled any woman, regardless of prior experience with electric lighting, to select a bulb to flatter her décor and complexion and easily install it into any standard fixture. Furthermore, the new bulbs provided indirect, colored lighting without need of special architectural coves, niches, or other masking devices—it was just a simple bulb that could be readily switched out if it was not pleasing. One of the first of these products was the “Softlight” incandescent bulb. Introduced by Sylvania Electric in early 1955, the Softlight was specially designed to “flatter home furnishings and occupants.”91 Coated with a pastel ceramic finish, the bulb produced a softer light than conventional frosted types and had the added benefit of altering the appearance of colors within its luminous reach. Sylvania’s Softlight bulb made yellow look orange, blue appear soft gray, and according to the Wall Street Journal, it gave a “warmer, deeper tone to orange and beige colors.”92 The New York Times reported in August of the same year that Sylvania’s new Softlight bulb “casts a mellow glow, without a pinkish cast, and is said to have flattering effect on complexions, wood grains of furniture and colors of fabrics.” The Times also promoted the bulb’s capacity to provide “indirect lighting without special fixtures.”93 Directly on the heels of Sylvania, General Electric released a “glamour pink” bulb in September 1955. Promoted nationwide, G.E.’s new product was praised by the Hartford Courant, which reported that the pink bulbs would “do more for a woman’s complexion than any lighting device since the candle.”94 Hartford Courant95 A photograph that accompanied the Courant column featured an attractive, smiling young woman holding a lit selection of G.E.’s new glamour bulbs, her face glowing warmly as if illuminated by candlelight.

In August of the following year, Westinghouse introduced the “Beauty Tone” family of pastel-tinted light bulbs. Like Sylvania’s Softlight and G.E.’s glamour bulb, the Beauty Tone bulbs were promoted for their decorative and beauty-enhancing effects. As the Chicago Daily Tribune reported, “The new ‘beauty tone’ bulbs can be used to refresh, intensify, lighten, or subtly alter existing textures and colors and can offer special flattery to the complexion.”96 Building on the “phenomenal” acceptance of the previous year’s pink-tinted light bulbs, Westinghouse introduced two additional colors, candlelight—flattering yellows, yellow-reds, and yellow-greens—and aqua—providing “an atmosphere of coolness,” and complementing blues and blue greens. The general manager of Westinghouse’s lamp division, F. M. Sloan, reported on the sweeping benefits of the new products to the Tribune, stating, “The various tinted light bulbs can be used to cool or warm a room or a corner, to express taste and personality, to create a special atmosphere for an evening or a season, or to recast a color scheme to accommodate new purchases or a change in furniture arrangement.”97

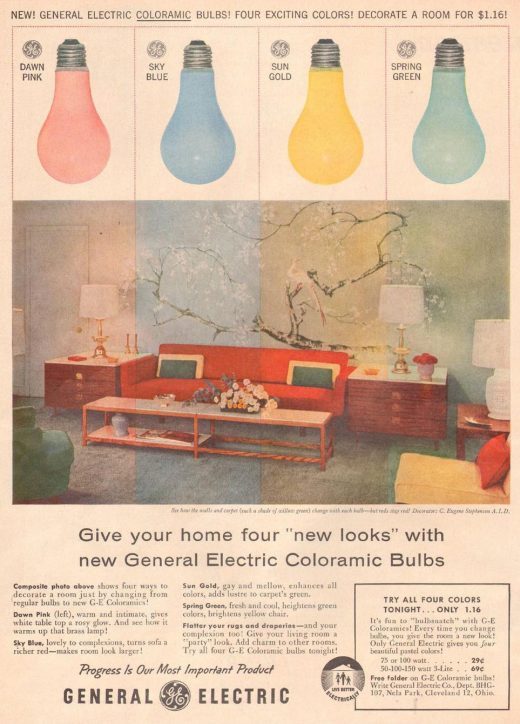

One month after Westinghouse released its extended product line of colored bulbs, General Electric introduced the “Coloramic” family in four shades: Dawn Pink, Sky Blue, Sun Gold, and Spring Green. In promotional materials intended for retail vendors, General Electric described the national advertising campaign planned for Coloramic bulbs during the 1956–57 selling season. The new product line was to be advertised in fashionable, full-color, full-page layouts in popular, nationally distributed magazines, including such titles as Better Homes and Gardens, The American Home, Life, and Look. These advertisements united discourses on female beauty and the decoration of the domestic interior with the satisfaction of a consumer lifestyle (fig. 7).

With increased profits through higher pricing on the colored bulbs, G.E. enlisted the support of retailers at the point of sale, providing special color display units to feature Coloramic products alongside examples of print and media advertising.98 Taking advantage of growing television audiences, G.E. also promoted Coloramic products in advertisements aired during the primetime family show Cheyenne, seen by roughly twenty-seven million viewers in 1957.99

An advertisement appearing in Look is typical of G.E.’s marketing campaign. Enticing readers to “Give your home four ‘new looks,’” the advertisement featured a stylish modern living room divided into sections, each corresponding in hue to one of the four shades of Coloramic bulb mentioned above (fig. 8).

Each section illustrated the dramatic effects of the colored light on the decor of the room, while the text below described each bulb’s decorative properties and benefits, which included imbuing the room with “charm” and flattering “your complexion too!”100 Carrying the “Live Better Electrically” logo, the advertisement associated the Coloramic products with the industry’s larger lifestyle campaign intended to dramatically increase the residential market for electrical energy consumption.

The marketing of colored incandescent light bulbs, in addition to appealing to traditional home decoration concerns, also capitalized on the intense interest in color as a consumer lifestyle choice in the postwar period.101 While color had long been a focal point of interest and concern for women, in terms of articulating and enhancing both one’s beauty and one’s interiors, perhaps in no previous era had color received such popular attention or exploitation as it did in the 1950s. Howard Ketcham, a leading color consultant to industry from the late 1930s onward, published Color Planning for Business and Industry in 1958. In the book’s nineteen chapters, Ketcham itemized the many uses and benefits of color in everything from display windows, to cosmetics, to advertising, to product design. Summarizing the importance of color in the book’s introduction, Ketcham argued, “So significant is the correct use and application of color today that it supplies an excellent earmark for the progressive, modern company. It often reveals whether a company is well-managed, well acquainted with the problems of modern merchandizing and well equipped to face competition.” Similarly, an article appearing in the Washington Post in 1951 called attention to swelling interest in color across industry and the public as the decade opened. In this syndicated story, the author instructed readers, “Colors can sell goods for manufacturers. They can make lives safer in a workshop. Color can actually change your life.”102 Interviewing Faber Birren, one of the nation’s leading industrial color consultants, the author described Birren’s belief in the benefits of color for the home and workplace but ultimately and most importantly for sales: “We buy food when it looks appetizing, clothes when they are becoming, and we insist that our homes be attractive and livable. Color is often the determining factor in what we select and what we reject.”103

Similarly, in 1953 the New York Times, covering recent marketing and advertising news, reported, “The influence of color in everything from supermarkets and plane and ship interiors to shirts and fountain pens is assuming greater importance yearly. The trend is expected to be accelerated in the consumer goods field as the country moves into an expanding buyers’ market.”104 The Times also consulted with Ketcham, who argued that the introduction of the color television was a major factor in the use of color in the marketing of products, particularly in the decorating, apparel, and home furnishing sectors. As Ketcham explained, marketers in these areas were “planning to present their products in full color on the screen.” Furthermore, colors were selected for products according to their gender appropriateness. Cosmetics were to be packaged in “soft feminine colors,” while razor blades would be packaged in “more masculine hues.”

It is not surprising, then, that General Electric first approached the market with its colored incandescent bulbs in “glamour pink,” or that Westinghouse responded with bulbs in “candlelight” and “aqua.” As a result of the research of Ketcham and other contemporary color consultants, manufacturers across the consumer goods industry expected that women would identify most closely with distinctly feminine colors. Furthermore, the pastel light bulbs enabled women to easily and affordably exchange one fashionable hue for another. The ability to quickly transform a look through color, whether personal or within one’s interior, had been a primary means of expressing personality since at least the 1930s. Thus the ease with which a woman could switch a light bulb and change the entire color palette of her environment was an obvious marketing advantage. General Electric’s Coloramic advertisements boldly proclaimed that for just a little over a dollar a homemaker could “decorate a room.” If color trends changed with the seasons, a woman could keep pace with the fashions by simply “bulbsnatching”—an act facilitated by purchasing Coloramic bulbs in a convenient four-pack carton.105

Whether by Westinghouse, Sylvania, or General Electric, across the industry the marketing of such products gathered together a number of primary concerns regarding interior decoration and personal beauty, providing a simple solution, coalesced within a single pastel-tinted light bulb. For at least half a century women had been instructed through etiquette manuals, home decoration guidebooks, advice columns, and other popular literature to embody their personality type in their attire and interiors, to color-coordinate and harmonize themselves within these spaces, to select cosmetics that would flatter their complexions, all the while being conscious of the light in which they would be seen, and in all of these choices to appear attractive and charming. With the introduction of colored incandescent light bulbs, women were promised a unified solution to these individual challenges. The soft-hued light suggested the possibility of instant transformation—harmonizing the color palette of the interior, enriching and glamourizing textiles and furnishings, providing atmosphere and charm, and in so doing, beautifying both the homemaker and her guests.106

Conclusion

The postwar American consumer market was a heady environment, redolent of the promise of a way of life unlike anything anyone had ever seen—more of everything, and everything better, brighter, and more colorful than before. Like Rosenquist’s F-111, American popular culture in the postwar period was suffused with ideas and imagery utilized in service of expanding the consumer marketplace. The promotion and marketing of gendered electric lighting applications and products was just one element in this dense commercial landscape. However, just as Rosenquist chose to use Coloramic bulbs as a metaphor for both the fragility and destructiveness of American culture, so too might we see the pastel-coated light bulbs of the mid-1950s as representative of the character of America’s postwar consumer culture and the industry that fed it. Electric light, especially colored light, was sold as an agent of glamour, flattering, harmonizing, and beautifying textiles, furniture, and people. The vibrant, multihued interiors featured in G.E.’s Coloramic advertisements suggested one variation on “good living” and the “way of life” that became central to US Cold War propaganda. Despite the monolithic nature of this concept of “good living,” there is little or no suggestion in the marketing rhetoric and imagery that it belonged to anyone other than white middle-class families. This was not an inclusive discourse, but one that assumed and inhabited an unnamed norm. Similarly the marketing of electric lighting to women leveraged long-held cultural constructions of gender roles, behaviors, and beliefs to situate these products within the daily life of women and in the social performance of femininity.

By all accounts these were powerful tactics predicated upon the core values of American female identity and agency—beauty, personality, charm, and hospitality. Whether the potent messages contained in the dialectic pairings of threats and promises in the discourse on electric lighting for women—ridicule/acceptance, discord/harmony, anemic/glamorous, illumurder/beautilluminate—resonated with its target audience is difficult to ascertain, but by the 1960s the domestic lighting market was breaking sales records. By 1961 half of all electric light bulbs sold in the United States were for residential use; and by 1965 over three billion light bulbs were being sold each year.107 Surely there were numerous forces contributing to this growth, including increased residential construction, growing diversity and availability of electric lighting products for the domestic environment, and unrelenting pressure from the industry itself on the American public to raise lighting level standards. The gendering of electric lighting with the intent of engaging female consumers is just one aspect of this bigger history. But, as I hope I have demonstrated, it is an important part of this history and one that allows key insights into some of the ways in which cultural beliefs about beauty, identity, and domesticity were reconfigured in white middle-class American society during the twentieth century.

Acknowledgement:

I would like to extend my gratitude to the anonymous reviewers at West 86th who provided me with excellent feedback and editorial guidance. Similarly, I would also like to thank Sandy Isenstadt for his helpful comments on an earlier version of this draft. And finally, I am grateful to Reggie Blaszczyk for organizing the 2012 Bright Modernity conference, where the seeds of this essay were first planted.

Margaret Maile Petty is a senior lecturer in the interdisciplinary Culture+Context program at the School of Design, Victoria University of Wellington (New Zealand). Her research investigates the discourse, production, representation, and consumption practices of the modern built environment, with a particular focus on lighting and interiors.

- 1. Arlene Dahl, “Let the Lighting Strike You Softly,” Washington Post, July 23, 1961.

- 2. I would like to thank Alex J. Taylor for calling my attention to the inclusion of the pastel-coated light bulbs in Rosenquist’s F-111. James Rosenquist, Painting Below Zero: Notes on a Life in Art (New York: Knopf, 2009), 160.

- 3. Evelyn Nakano Glenn, “The Social Construction and Institutionalization of Gender and Race,” in Revisioning Gender, ed. Myra Marx Ferree, Judith Lorber, and Beth Hess, 3–43 (Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press, 2000). Among the many excellent and diverse studies examining gender, race, and class in the United States during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries are Gillian Brown, Imagining Self in Nineteenth-Century America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990); Gail Bederman, Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880–1917 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995); Joan W. Scott, “Some Reflections on Gender and Politics,” in Ferree, Lorber, and Hess, Revisioning Gender, 70–98. On women and the history of business, see Alice Kessler-Harris, “Ideologies and Innovations: Gender Dimensions of Business History,” Business and Economic History 20 (1991): 45–51; and Wendy Gamber, “Gendered Concerns: Thoughts on the History of Business and the History of Women,” Business and Economic History 23 (Fall 1994): 139–40.

- 4. Richard Hirsch, Technology and Transformation in the American Electric Utility Industry (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 1–46.

- 5. Richard Dyer, White (New York: Routledge, 1997), 9.

- 6. Alice Friedman, American Glamour and the Evolution of Modern Architecture (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010), 13–14.

- 7. Stephen Gundle, “Hollywood Glamour and Mass Consumption in Postwar Italy,” Journal of Cold War Studies 4, no. 3 (Summer 2002): 95–118.

- 8. On the deconstruction of monolithic representations of American women as complacent housewives, see Joanne Meyerowitz, “Beyond the Feminine Mystique,” in Not June Cleaver: Women and Gender in Postwar America, 1945–1960, 229–62 (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1994).

- 9. Elsie de Wolfe, The House in Good Taste (New York: Century Co., 1913), 73.

- 10. Thomas E. Hill, Hill’s Manual of Social and Business Forms (Chicago: Hill Standard Book Co., 1885), 176.

- 11. A. Ashmun Kelly, “Modifications in Colors Produced by Colored or Artificial Lights Falling upon Them,” Decorator and Furnisher 25, no. 4 (January 1895): 143–45.

- 12. Ibid.

- 13. Beverly Gordon, “Woman’s Domestic Body: The Conceptual Conflation of Women and Interiors in the Industrial Age,” Winterthur Portfolio 31, no. 4 (Winter 1996): 281–301, quote on 286.

- 14. Antoinette Donnelly, “Good Lighting Is Half the Trick in Applying Makeup,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 5, 1926.

- 15. Kathy Peiss, “Making Up, Making Over,” in The Sex of Things: Gender and Consumption in Historical Perspective, ed. Victoria de Grazia, 311–35 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1996).

- 16. Ibid., 320–22. On the close correlation between beauty, glamour, and race and the promotion of female performers in the United States in the early decades of the twentieth century, see Linda Mizejewski, Ziegfeld Girl: Image and Icon in Culture and Cinema (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999).

- 17. Peiss, “Making Up, Making Over,” 322.

- 18. Henry Urbach, in his study of Parisian nocturnal culture in the 1920s and 30s, argues for the central role of electric light in the “renegotiation of feminine identity” and the loosening of essential categories of gender as a “more fluid and performative notion of identification emerged” against the electrified backdrop of “sparkle and exposure, disguise and dazzle.” Henry Urbach, “Dark Lights, Contagious Space,” in InterSections: Architectural Histories and Critical Theories, 150-60 (London: Routledge, 2000).

- 19. See, for example, Donnelly, “Good Lighting Is Half the Trick,” 27.

- 20. See Antoinette Donnelly, “Cosmetics Drive Away the Blues,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 12, 1927, and “These Little Tricks Will Add Beauty to the Eyes of a Femme,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 25, 1928. In addition to the New York Daily News Donnelly wrote for a number of other daily newspapers and was credited with receiving as many as ten thousand letters a day. For biographical details on Donnelly, who also penned women’s advice literature under the name Doris Blake, see “N.Y. News Columnist Antoinette Donnelly Dies,” Washington Post, Times Herald, November 17, 1964; and Kathy Peiss, who also briefly discusses Donnelly in “American Women and the Making of Modern Consumer Culture,” Journal for Multimedia History 1, no. 1 (Fall 1998), electronic text accessed at http://www.albany.edu/jmmh/vol1no1/peiss-text.html#fn5r.

- 21. Donnelly, “Good Lighting Is Half the Trick,” 27.

- 22. Antoinette Donnelly, “Antoinette Gives Several Practical Rules for Makeup,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 23, 1932.

- 23. General Electric, advertisement for Edison Mazda lamps appearing in Better Homes and Gardens, April 4, 1931, inside front cover.

- 24. “Six Original Designs for That Wise Form of Vanity, the Dressing Table,” Vogue 64, no. 10 (November 15, 1924): 42-43.

- 25. Donnelly, “Antoinette Gives Several Practical Rules.”

- 26. Mamye Ober Peak, “Hollywood’s Master of Make-Up,” Hartford Courant, February 3, 1929.

- 27. See Warren Susman, “‘Personality’ and the Making of Twentieth-Century Culture,” in New Directions in American Intellectual History, ed. John Higham and Paul Conkin, 214–22 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979); and Simon J. Bronner, ed., Consuming Vision: Accumulation and Display of Goods in America, 1880–1920 (New York: W. W. Norton, 1989).

- Sarah Berry, “Hollywood Exoticism: Cosmetics and Color in the 1930s,” in Hollywood Goes Shopping, ed. David Dresser and Garth S. Jowett, 108–38 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), quote on p. 111.

- 29. Peak, “Hollywood’s Master of Make-Up.”

- 30. Ibid.

- 31. See, for example, Donnelly’s advice regarding the adoption of theatrical make-up and lighting techniques to make “a lady what she ain’t,” in Antoinette Donnelly, “Theater Has Makeup Tips for Amateurs,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 10, 1940.

- 32. Rosalind Shaffer, “Makeup Expert Able to Paint Personality on Faces: Features of a Subject Serve as a Canvas,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 25, 1935.

- 33. Carolyn van Wyck, “Photoplay’s Own Beauty Shop,” Photoplay, January 1939, as quoted in Berry, “Hollywood Exoticism,” 116.

- 34. Martha Parker, “Powder for Beauty,” New York Times, August 1, 1943.

- 35. Peiss, “Making Up, Making Over,” 328–29.