This review originally appeared in the Vol. 25 No. 1 / SPRING-SUMMER 2018 issue of West 86th.

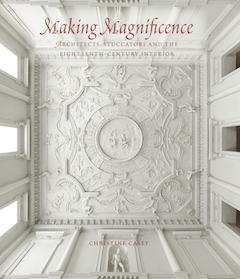

Making Magnificence: Architects, Stuccatori and the Eighteenth-Century Interior

Christine Casey

New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2017.

328 pp.; 175 color and 50 b/w ills.

Cloth $75.00

ISBN 9780300225778

In October 1750, George Stone, the Archbishop of Armagh, accompanied by William and John Ponsonby, the Earl of Bessborough’s sons, made a hasty and unannounced visit to the Earl of Tyrone’s mansion, Curraghmore House, to view the library with its new stucco decoration by the Lafranchini brothers. Tyrone was then in Dublin. His agent wrote that the visitors had “made the tour very strangely.” They had been in such a blinding hurry that they did not even wait for the maid to unlock the front door; instead they clambered through an open window to admire the new work. This rather bizarre evidence of enthusiasm for the Lafranchini brothers’ stuccowork is recounted in Christine Casey’s impressive new monograph, Making Magnificence: Architects, Stuccatori and the Eighteenth-Century Interior. Casey documents the migration of several generations of enormously skilled stucco artists from the area around Lake Lugano across Europe to Rome and Turin, to Vienna and Bonn, and to London and Dublin. Their virtuosic modeling of lime plaster mixed with gypsum, water, sand, and animal hair structured the walls, domes, vaults, and ceilings of eighteenth-century palaces, houses, and churches, transforming them into rich fields of plastic decoration and figuration. In Britain, the superb richness of stuccoed interiors provided striking contrasts with the elegant but restrained architecture of neo-Palladian mansions, complemented by the costly and glamorous furniture, paintings, and fittings the houses also contained. William Kent’s lavish baroque furniture or the later, French-inspired rococo work of Chippendale, for example, provided additional expensive, ostentatious manifestations of magnificence.

As a medium, stucco connected architecture with fine art and furniture. Sometimes it constituted a direct interface between architecture and painting, as when stucco frames imitating stone enclosed quadri riportati (fictive easel paintings). Sometimes figurative stucco replicated painted compositions: it was frequently based on engravings after the Carracci, Pietro da Cortona, and Simon Vouet and thus translated—or transmuted—“fine” into “decorative” art (107, 231). Casey includes spectacular three-dimensional images molded in stucco, including the work of G. B. Artari at Fulda Cathedral (1707–12), Diego Francesco Caloni and Donato Riccardo Retti at Schloss Ludwigsburg (1715–16), Giuseppe Artari in the Council Chamber of the Hôtel de Ville in Liège (1718–19) and at Upton Hall in Northamptonshire (1737), G. B. Bagutti at Mereworth Castle (ca. 1725), Antonio Bossi at Ottobeuren Abbey (ca. 1727), and Bossi and Carlo Maria Pozzi in the Hofkirche at Würzburg (1736–38). Although Casey does not dwell on the impact of their work, such images may have prompted sculptors of the next generations to try to carve similarly dynamic and fluidly pictorial figures in the more elevated medium of marble. The most accomplished modelers of stucco, the figuristi, themselves sometimes aspired to the higher status of marble sculptors and very occasionally even signed their works. Giovanni Battista Artari, for example, proudly signed the branch under the foot of his statue of St. Sebastian in Fulda of ca. 1710: “G. B. Artarius Helvet[ic]us Luganensis F[ecit]” (fig. 64).

It is the stuccatori who are the heroes of Casey’s engaging monograph, the maestri dei laghi(masters of the lake) who exported their skills to the North. Their names are not well known to art or design history, in spite of the impact of their work on the period’s architecture. The stucco workers generally returned to their homes near Lake Lugano out of season, that is to say, between November and March. Some faced great risk: at the turn of the century, Giacomo Ghezzi and his son Francesco Antonio, who had been working in Austria and Poland, were killed in an avalanche on their way through the St. Gothard Pass to their home village of Sigirino (80). Some of them found partners in the North, like Francesco Antonio Vassalli, who married an Englishwoman and retired with her in Riva San Vitale, or Giuseppe Artari, who married a German and died in Bonn in 1771. Others suffered from acute homesickness and mancanza, the longing for their loved ones back home.

Casey shows that their craft was effectively without a written theoretical framework, and though some stuccatori had training in disegno (drawing), only a few maestri—for whom the skill was a necessary means of winning commissions and demonstrating their design proposals—were particularly competent draughtsmen. Instead, the artists preferred to sketch out figures in freehand on the wall or ceiling surfaces, or even to mold terracotta models for their patron’s approval (109), just as Louis-François Roubiliac later did for his sculptural commissions in England. What is clear, though, is that the stuccatori were more skilled in figure modeling than most British artists. In 1748, Lady Luxborough observed that the Worcester plasterer John Wright employed an Italian “where elegance is required.” It was their greater skill levels, placing them at a distinct advantage over indigenous competitors, as well as the demand for their work, that drew the maestri northward (120, 207). In Britain, of course, the plaster ceiling decorations of Elizabethan, Jacobean, and Caroline mansions provided important precedents for (and contrasts with) these later figural compositions on mantelpieces, walls, and ceilings—though, oddly, this is not a subject Casey discusses.

Her principal focus, she states in the introduction, is on seven individuals who came to Britain and Ireland in the eighteenth century: Giovanni Bagutti, Giuseppe Artari, Francesco Antonio Vassalli, Giuseppe Cortese, and the Lanfranchini brothers, Paolo, Filippo, and Pietro. We meet some of them briefly before a proper introduction in chapter 5. This is a direct consequence of the book’s panoramic structure. The first three chapters provide a broad and systematic introduction to the subject. The first examines the relationship between architecture and stucco decoration, including observations on the way that architects managed the stucco artists. The second discusses the geographical and social background of Luganese stuccatori (there is a useful map showing the origins of the British stuccatori and their associates, which has for incomprehensible reasons been placed as an appendix on p. 294, after the notes). Chapter 3 considers the stucco industry—the means by which artists were trained, studio production, contracts, and wages. The second part of the book considers the work of the stuccatori in Germany and Austria, before Casey turns to those who worked in Great Britain and Ireland. In chapter 4, she analyses the German work of Giovanni Battista Artari, the father of Giuseppe Artari, and the evidence for the relationship between the Artari and Vassalli workshops before their collaboration in Britain. Here Casey draws together a great deal of new research and seems an entirely sure-footed guide to a series of major projects, such as those at Schloss Rastatt, Fulda Cathedral, and Ottobeuren Abbey. It is in chapter 5 that Casey looks at the work of the stuccatori in England, focusing on the work of Bagutti at houses such as Castle Howard, Cannons, and Mereworth Castle, his collaboration with Artari at Moor Park and perhaps at Barnsley Park, Artari’s work at Upton Hall, Clandon Park, and Houghton Hall, and Vassalli’s at Mawley Hall, Towneley Hall, Wentworth Castle, and elsewhere. In each case the documentary and stylistic evidence is carefully and persuasively evaluated. In her final chapter, Casey traces the careers of the Lanfanchini in Ireland with a similar enthusiasm to that of Archbishop Stone, beginning with their stunning debut stuccoing the walls, coving, and ceiling of the Eating Parlour of Carton House in County Kildare in 1738–39. Their status must have been elevated by the fact that they were the only stuccatori to develop careers in Ireland; an inflated sense of Filippo Lafranchini’s self-worth is perhaps suggested by his reported “impertinence” in 1759. Perhaps he objected to living in Ireland, as Lady Kildare complained that foreign gardeners did.

Throughout, Casey’s empirical research is exemplary, but she also pays proper homage to her predecessors, most notably Beard. The book is written with an entertaining zest, though there are a few clumsy sentences, of which this is fortunately by far the worst: “Richard Sennart’s attractive argument for the emulation of craftsmanship as a means of reconfiguring society’s over-emphasis on cerebral achievement is not supported by such a headlong rush to horror vacui” (36). The illustrations, as one would expect from Yale University Press, are frequently excellent, but some—e.g., figs. 229 and 239—are so small as to be of nugatory value, and fig. 141 is rendered entirely useless by the absence of any numbers on the ground plan. I noticed very few typographical errors—on p. 184, 1721 was misprinted as 1921—and the index veers on occasion out of alphabetical order. Nonetheless, this is an impressively researched, well-produced monograph, displaying a magisterial knowledge of the subject.

Phillip Lindley is Excellence 100 Professor of the History of Art and Architecture at Loughborough University in the UK. He was previously professor of art history at the University of Leicester, where he founded the Centre for the Study of the Country House.