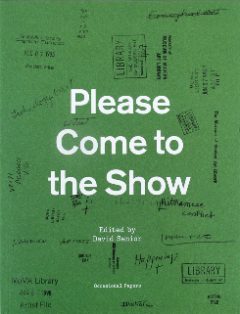

Please Come to the Show

Edited by David Senior

London: Occasional Papers, 2014.

160pp.; color ills.

Paper £17.50

ISBN: 9780956962379

I recently purchased a used copy of the art historian Ursula Meyer’s Conceptual Art (1972) on Amazon for £1.76, plus international shipping and postage. It arrived in the post a week or so later after being dispatched from New York to my home in London. When I opened it, I noticed that the inside cover was stamped with the name and mailing address of the previous owner: Dan Graham. The artist was using a P.O. Box at Knickerbocker Station on East Broadway in Manhattan when he owned the book. The rubber stamp of his address on the inside cover had not come through entirely on first impression, so the “8” in “Box 380” was overwritten by hand in black pen, presumably by an assistant, or perhaps by the artist himself. The unexpected coincidence of obtaining a text with markings, however small, by Graham points to a theme running through the new volume published by Occasional Papers, Please Come to the Show (2014)—that is, the transition of printed matter surrounding art exhibitions from ephemeral communications material to art historical objects. Is all of the stuff that surrounds exhibitions and art practices, particularly those based in conceptual ideas and not in material perceptions, the stuff of art? What historical value does it add to our understanding of the art practices and the movements, and discourses around them?

Please Come to the Show is edited by David Senior, bibliographer at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) library in New York. Senior has selected from the MoMA library collection a wide range of printed matter intended as ephemera—exhibition announcements including postcards, flyers, and posters—that has entered the museum system by way of correspondence, and that has been subsequently archived and occasionally subject to “overactive stamping practices” (63). After nearly a decade of gallery announcements declaring cessation of sending printed invitations, Senior observed a change in the way in which we are invited to exhibitions. This inspired Senior to present his selection of the material as an exhibition, which he first did in 2013 in the MoMA library. With e-mail, the art newsletter e-Flux, and electronic mailing list software, invitations are often unviable or undesirable, costly both monetarily and environmentally. What has been the result of this change in communications practice?

Senior’s method of research is, by necessity, very material: he physically sifted through boxes of curators’ files, invitations, and archives. His methodology is also voyeuristic, for Senior was viewing not only the invitations and announcements, but the correspondence written on them by the sender or receiver. The material is presented as uncaptioned, unframed, often full-bleed images, organized roughly chronologically, from the 1960s to the present, beginning with a Gustav Metzger announcement for auto-destructive art on London’s South Bank. New essays by Senior, as well as artists’ book advocate Clive Phillpot, artist Angie Keefer, and typographer Will Holder, are interspersed through images of announcements in the book. Together these explore the material that is often intended to be thrown away but which provides the first interface between the artist and an audience. Published following the exhibition of the material at the MoMA library, which then traveled to the Exhibition Research Centre in Liverpool, England, the book provides a valuable document to give public permanence and materiality to these artifacts of artists as well as to the artists’ communities, contexts, and communication.

Senior’s essay gives the book its title and explores numerous valuable questions around these items, namely: what happens when this material shifts from printed matter to archived, art historical object? Most of the items (to call them “works” seems heavy-handed) selected are from 1960s and 1970s New York: a period of rapid productivity defining much of contemporary practice through happenings, events, performances, and exhibitions that tested the parameters of ideas-based practice. This movement of the first period of Conceptual Art in America was defined by a removal of the object status of the artwork, and a challenge to the art institution. It seems contradictory that an early career exhibition invitation sent to the critic Lucy Lippard in 1982 by the late artist David Wojnarowicz—who wrote earnestly but cautiously on the card: “Lucy Lippard, Hope you can catch this show. David”— ended up stamped, archived, and catalogued for this future use. This suggests an often-overlooked function of the museum machine, whereby despite whatever counternarrative the avant-garde may produce, someone in the museum is collating it as a document of the present. On the announcements, years or cities are often left out, as such information would already have been apparent to the receiver. The ephemeral nature and local specificity of the pieces are reiterated when they become archival objects. Senior highlights a Dan Graham postcard for a performance at the Royal College of Art, on which “ᴛᴏᴅᴀʏ” is inscribed and underlined by the anonymous recipient. The text on the white card, typewritten in black with only brief information conveying the location and time of the performance along with Graham’s name, highlights the temporality of the communication and gives an aura-esque flash of the receiver, who may or may not have made it to the show, and of Graham in his equally fleeting presence at the venue. Such flashes and personal injections into the texts surrounding artworks are lost with digital media.

Holder focuses his essay on the collapsing of instruction and document, reading and writing in the example of a line of code and its displayed text in a digital announcement. The breadth of examples of announcements assembled in the book reveals shifts and trends in graphic design as a responsive medium, and art as a field responding to cultural changes by way of graphic design. Text-heavy documents and posters give way to minimal photostats; found and appropriated imagery sit alongside announcements made of collaged and handwritten text in a DIY aesthetic of the punk era. Some announcements—Barbara Kruger’s for one—mirror the artist’s use of text in her visual practice. All speak to a period before brand identity was part of the gallery- and museum-industry lexicon, and the graphic design, broadly speaking, responds to the artists and their work.

Exhibition announcements are testaments to exhibitions held, irrespective of the show’s subsequent importance or critical impact. In a predigital age, if an exhibition is not reviewed or is without catalogue, then little evidence remains to prove it happened. The collated material in Please Come to the Show points out exhibitions and elements of artists’ practices often overlooked and not written into an artist’s biography. Two announcements for exhibitions of Kruger’s artwork are presented in a Futura bold oblique typeface and monochromatic colorway with punches of red, echoing her widely recognized visual style. These announcements sit on the same page as one curated by Kruger, Artists’ Use of Language, at Franklin Furnace, then in SoHo. Yet Kruger’s curatorial projects (she also organized Picturing Greatness at MoMA in 1988) are rarely referenced in her artist’s CV, though her experimentations have been influential on curators.1 As historical documents, the announcements record shifts in style and printing technologies as well as the lexicon surrounding exhibitions. Kruger is without title on the exhibition announcements for her solo shows, but she is noted to have “curated” (124) exhibitions on other announcements; whereas French artist Daniel Buren is the “person responsible” (88) for an exhibition of one of his films in 1970, and critic and curator Lucy Lippard “compiled” (87) the works for an exhibition benefiting the Art Workers Coalition at Paula Cooper Gallery in 1969. Such credits highlight a period before “curator” became synonymous with all exhibition-making practice, regardless of whether there was a collection with which to curate, or if the project instead entailed gathering material and works from outside an institution.

Keefer questions in her essay: “What’s the difference between an advertisement (for a show or anything else) and an announcement?” (33). Critical of most artists’ announcements making an “upside-down inside-out peek-a-boo made-you-look confrontational paradigm” (34), Keefer suggests that though an announcement may “trot ahead” (33) of the main event, it is still part of the same whole, the artist’s oeuvre. It is not uncommon to save a few announcements that hold place on a desk long beyond the close of an exhibition. Usually these announcements act as a reminder of sorts. Others are a work of art of sorts. I have had one such announcement by the curator and artist Matthew Higgs around my desk since 2008, where it occasionally resurfaces as a bookmark. From an exhibition at Wilkinson Gallery, it says simply in a white sans-serif bold typeface on a black card: “Art is To Enjoy.”

The lengthiest announcement presented in the book is for an Andy Warhol exhibition held at the Stable Gallery in New York in 1962. Nine pages long, the typewritten text announcing Warhol’s exhibition is a photostat reproduction of a term paper by an undergraduate student named Suzy Stanton. She wrote the paper, “On Warhol’s ‘Campbell’s Soup Can,’” for a class on art and communications at Bennington College in 1962. Her teacher, Lawrence Alloway, showed Stanton’s paper to Warhol, who then used it as an announcement. Apart from its inclusion in the book, we can identify this as an exhibition announcement only from a rubber stamp noting brief exhibition details on the final page of the paper. Stanton’s paper constructs a scenario of a fictional studio visit with Warhol, during which hypothetical conversations between sixteen students and Warhol unfold on topics that include his work and his relationship with soup. The photostat represents it complete with Alloway’s handwritten comments in the margins ranging from “wowie,” to “great conclusion: I should have seen it coming,” to a Pop-art-like “Pow!” alongside a particularly succinct point. (Alloway, a critic, was responsible for coining the term Pop art.)2 Senior managed to locate Stanton, who prefaces the announcement’s reproduction in the book with a brief text clarifying how it came to be used by Warhol. While she was studying abroad in Mexico, the artist obtained her permission for its reproduction, offering a painting in return. After returning to the United States, and then convalescing from food poisoning for several months, Stanton visited Warhol’s famous studio to receive her painting, only to be left waiting for hours while the artist ignored her as he viewed newly obtained pornographic movies. Finally leaving, bored, embarrassed, and unenthused, Stanton found her mythic appreciation of Warhol replaced by a realization that dispelled any illusion of connection through their shared text. Stanton’s experience debunks the myth machine that many galleries churn around artists.

Reviewing the material in Please Come to the Show one cannot help but wonder: how do museums archive such stuff now? Instead of desks cluttered with announcements, we have e-mail in-boxes littered with e-flyers. Museums no longer collect the majority of announcements. As fewer exhibition invitations are done in printed form, the book reflects on the change in correspondence and ephemera some ten years after the switch from printed communications to digital. Though the printed matter that composes these announcements was not intended to be archived, it nonetheless possesses the material qualities that enable it to be so. Anthony Hudek addresses this idea in his chapter in the volume on “Library Art.” Senior sees exhibition announcements as a rare moment in which artists reach beyond their work to attempt to communicate with an audience, imploring them to come to see their work. With the shift to digital, we are losing announcements representing not simply graphic design artifacts, but markers of the communities and networks surrounding artworks. What then, if anything, will come to replace it?

Kim Dhillon is a writer and artist currently completing a thesis on text art in contemporary visual practice since Conceptualism at the Royal College of Art, London.

- 1. See “Barbara Kruger and Iwona Blazwick in Conversation,” Modern Art Oxford, 27 June 2014, https://soundcloud.com/user283658505/barbara-kruger-modern-art-oxford-27614.

- 2. See entry for Lawrence Alloway in Dictionary of Art Historians, http://www.dictionaryofarthistorians.org/allowayl.htm, retrieved 26 August 2014.