This review originally appeared in the Vol. 19 No. 1 / Spring 2012 issue of West 86th.

Exhibition:

Vishnu: Hinduism’s Blue-Skinned Savior

Frist Center for the Visual Arts, Nashville, TN

February 20—May 29, 2011

Brooklyn Museum

June 24—October 2, 2011

Catalogue:

Vishnu: Hinduism’s Blue-Skinned Savior

Edited by Joan Cummins

Frist Center for the Visual Arts, Nashville, in association with Mapin Publishing, 2011.

296 pp; 236 color and black-and-white illustrations

Cloth $75.00

ISBN: 9781835677093

Paper $40.00

ISBN: 193567708X

Let us tell them what these works of art are about and not merely tell them things about these works of art. Let us tell them the painful truth, that most of these works are about God, whom we never mention in polite society. Let us admit that if we are to offer an education in agreement with the innermost nature and eloquence of the exhibits themselves, that this will not be an education in sensibility, but an education in philosophy.

—Ananda Coomaraswamy, “Why Exhibit Works of Art?”1

In the last few decades there have been several major exhibitions devoted to Hindu deities, including Devi (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011; Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, 1999), Shiva (Museum Rietberg, 2008–2009; Asia Society for the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1981), and the deities as a group (New Orleans Museum of Art, 2011; National Folk Museum of Korea, 2011; Freer|Sackler, 2002–2003).2 Until very recently, however, there has been no major museum exhibition devoted to the most readily and widely worshipped deity in the Hindu pantheon, leaving a Vishnu-shaped void in the U.S. exhibition program. Vishnu: Hinduism’s Blue-Skinned Savior, organized by the Frist Center for the Visual Arts and guest curated by Joan Cummins of the Brooklyn Museum, filled this gap. The exhibition contained over 170 works, selected by Cummins from museums and private collections for both their artistic merit and their novel or unusual treatments of the subject matter. It was accompanied by a 296-page catalogue with essays by scholars of art history, religion, and anthropology and including 217 color and 19 black-and-white illustrations and 1 map.

The exhibition and its catalogue add an interesting chapter to the ongoing dialectic between aesthetics and history. Although art historians underwent a self-proclaimed crisis of consciousness3 with regard to the training of a Western lens upon an exotic “other,” it is not yet clear that this has significantly lessened the tension between ethnographic displays and a “white cube” of pure aesthetic consideration–especially when dealing with religious art. Western methods of museum exhibition of Indian religious art are also currently the subject of much debate in Baroda, New Delhi, and Calcutta.4 Between these two poles lies an interesting space for negotiation when introducing an uninitiated American public to the Vaishnavite tradition(s). Cummins’s consideration of these issues is demonstrated by the conceptual organization and physical layout of the exhibition, the selection of the objects, and the choice of the catalogue authors (Doris Meth Srinivasan, Leslie C. Orr, Cynthia Packert, and Neeraja Poddar, as well as Cummins herself). Many of the sculptural works in the Brooklyn Museum’s galleries come from temples devoted to Vishnu and, as was briefly explained in the label text, were honored in ritual processions. The catalogue essays expand upon the living traditions that surround these objects of devotion, supplementing the exhibition’s stated goal of initiating a new audience to the “multiplicity and grandeur” of Hindu art.5

The Image of Vishnu: Brooklyn Installation

A typical museumgoer’s experience of the religious objects on display is far different from the experience of such works in their original context. Yet, subtle and conscious organizational attention in Vishnu lessened this conceptual distance. An especially striking sculpture of Vishnu’s animal mount and faithful devotee, Garuda, was placed across from Vishnu in the gallery much as he would have been positioned in situ. This Garuda, from the Rubin Museum of Art collection (fig. 1), retained the remnants of roli–a powdery substance used to adorn the gods during puja, or devotional ritual–bringing the viewer’s attention to the original context.

The living tradition of the works was reiterated in label text throughout the gallery and especially through sections devoted specifically to the worship of Vishnu (fig. 2), including popular print culture posters with Hindu subject matter for home and office shrines. After having traveled through the galleries, the viewer encountered a prominently displayed disclaimer in large-point wall text paying respect to the limitless avenues of worship and numerous Hindu practices that do not involve art objects at all (for example, yoga, meditation, music and dance, charitable acts, daily prayers, and festivals). This disclaimer referred the visitor to the associated living traditions that could not be included in the exhibition and explained that the ideas presented in the exhibition inherently relied on works of art as a springboard for discussion. Interesting additions to the programming at the Frist were a concurrent exhibition, Hindu Home Shrines: Creating Space for Personal Contemplation, and an audio tour for the Vishnu exhibition that modeled a classical Hindu teacher-student interaction.6 At the Brooklyn Museum, the Target First Saturday event featured art-making, storytelling, and traditional and contemporary Indian music, and there was a series of two-hour yoga workshops that began with a tour of the exhibition and culminated with yoga practice in the Brooklyn Museum’s fifth-floor rotunda.

The most influential underlying feature of the exhibition, in terms of interpretation, was its thematic organization, which reflected the Indian concept of cyclical time. Freed from chronology and given only rare descriptions of historical time within the exhibition, the viewer could concentrate on the folk and contextual stories. This nonlinear organization also allowed for comparisons of different depictions of the same mythological event–giving a glimpse of Cummins’s taste for the rare and unusual (as exemplified by her selections).

The exhibition, however, did not overwhelm the viewer with text, offering rather a balance between art and accompanying description. Doris Meth Srinivasan’s catalogue essay, “Becoming Vishnu,” injects chronology into a timeless exhibition by describing the evolution of Vishnu, from a Vedic player to Supreme Being, through textual sources (Rig Veda and Bhagavad Gita) and with visual examples. The development of Vishnu’s awesomeness from more humble beginnings was also alluded to in the first section of the exhibition–the discus he is often depicted with is traced from Vishnu’s Vedic appearance as one of several solar deities. Displayed in the same section, Vishnu in His Cosmic Sleep (circa twelfth century) (fig. 3) exemplified the scope of Vishnu’s power and influence. The story of Vishnu reclining on the serpent Shesha illustrates the very cosmology of the universe: during the god’s rest on a turbulent and chaotic ocean, the creator god, Brahma, sprouts from his navel, and the origin of the universe is witnessed in this scene by the avatars of Vishnu along with the nine planetary deities.

The Avatars of Vishnu

Vishnu is the Hindu deity most often associated with avatars because he has so many (there are varying interpretations of their number) and because their sole purpose is the preservation of the world–so often in mortal danger from destructive demons. The exhibition included ten of these avatars, from Matsya, the fish, to Kalki, an avatar of the future. Offering an effective metaphor for the nature of avatars, the label text stated, “These earthly manifestations are less glorious than the god, have finite bodies, and are usually mortal. Vishnu’s descent from the heavens in the form of an avatar may be compared to reaching his hand down; the hand is fully Vishnu, but it is not the god in full.”

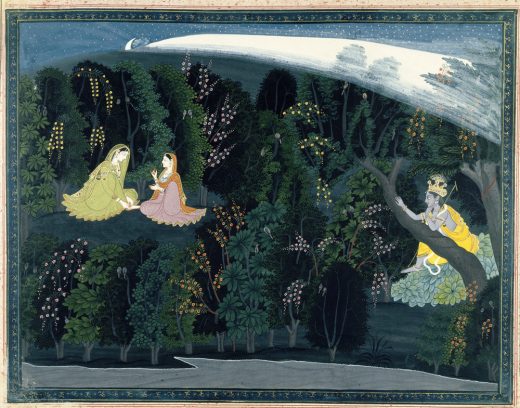

A notable anomaly is the avatar Krishna, who is often considered a god in his own right. For his followers, Krishna is the Supreme God. His legendary romance with the cowherd (gopi) Radha has for centuries been immortalized in a wide range of mediums. Romantic love is used as a metaphor for spiritual devotion. The Krishna area of the avatar section was flush with illuminated manuscript paintings,7 reflecting the abundance of Krishna worship. An especially beautiful page from a Gita Govinda manuscript (fig. 4) captures Krishna gazing longingly after Radha. Their bodies glow in the moonlight, and the flowering plants and pairs of birds anticipate the reunion of the lovers.

The Avatar and the iPad: Technology Inside and Outside the Galleries

At the entrance to the exhibition in the Brooklyn Museum, visitors were invited to take a short quiz to identify themselves with the traits of one of Vishnu’s avatars and then to take with them an avatar tag with art by Pixar animator Sanjay Patel. Throughout the exhibition, visitors were encouraged to identify their host avatar through their iconography. This exercise in recognition (with more than a hint of appeal to personal vanity and an oblique reference to the personal nature of bhakti) offered a change of pace in the second section of the exhibition. Potentially overwhelmed by the images and legends of Vishnu, viewers suddenly had an opportunity to learn through play with strategically placed iPads–the reward being an extra tidbit of information about the piece behind the device (fig. 5).

At the very end of the exhibition, visitors were then invited to respond to images of “their” avatar and choose their favorite representations of that avatar included in the exhibition.8 This list of avatar selections was sent by e-mail to visitors, who were able to keep up with the current tally of favorites by a link to constantly updated feedback software. For an exhibition with the goal of initiation, this simple use of technology effectively quadrupled the viewing time of a particular work by the average visitor.9

The Worship of Vishnu: Living Traditions of India

The final section of the exhibition was the most divergent and innovative. The variety of works on display, from a miniature shrine made of precious metals and gems to mass-produced color prints from the twentieth century, gave a sense of the immeasurability of the ways of worship and living tradition. Catalogue essays by Leslie Orr and Cynthia Packert expand on southern and northern traditions of bhakti and offer additional content. Orr’s essay, “Vishnu’s Manifestations in the Tamil Country,” expounds on unique connections of Vishnu to the Tamil landscape, particularly the development of the Srivaishnava tradition peculiar to the region. Orr traces the origins of religious Tamil poetry, dedicated to Vishnu, composed between the sixth and ninth centuries by twelve poet-saints (alvars), whose quests for encounters with Lord Vishnu led them to 108 sacred places, or divyadeshas. The poems of these saints are considered to be the “Tamil Veda.” The legacy of this literature inspired a wealth of philosophical works and commentaries on the alvars’ poetry, and the importance of the divyadeshas and the culture of pilgrimage grew over time.

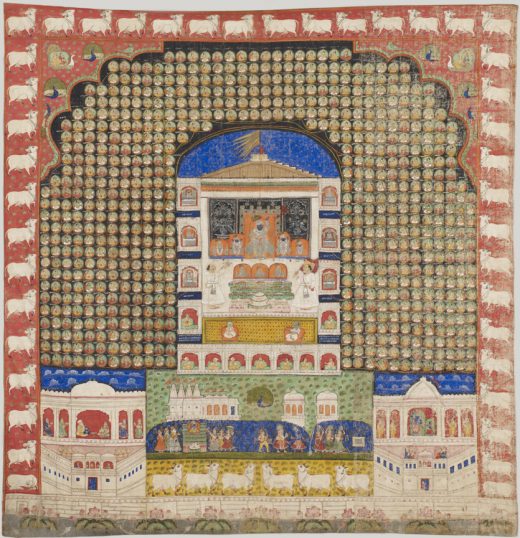

Similarly, in her essay, “Networks of Devotion: The Art and Practice of Vaishnavism in Western India,” Packert discusses a unique “self-manifestation,” or divinely created sculpture, and shows how devotional practice manifests itself in the region of Rajasthan. Packert gives the historical context for the development of Shrinathaji–a particular black stone form of Krishna uncrafted by human hands, a svarupa that was divinely revealed under specific circumstances over a long period of time. She recounts the story of Shrinathji’s fifteenth-century discovery as a manifestation of Krishna by the child Vallaba, carefully citing the circumstances that led to the god’s constant care by a hereditary priesthood. (According to Packert, this priesthood, descended from Vallaba, continues to care for Shrinathji to the present day.) A svarupa is fully present at all times; it is not just a sculpture, but a divine presence inherent in the material. Shrinathji’s care is a meticulous and rich religious practice involving dressing, ornamentation, oblations of food and drink, and all manner of diversions to keep this child form of the god content. In a picchawai, or decorative background cloth for a shrine image, which depicts the Annakut festival, images of Vallaba’s descendents are seen alongside Shrinathji at the center and a group of six other svarupas that appeared to the poet-saint (fig. 6). For each of these svarupas, there is a sectarian group with similar liturgical practices and ritual care for their own manifestation of Krishna.

When in view of the public, the most important activity for devotees is darshan, to see and be seen by the gods. By carrying out this act of worship through seeing, the devotee gains the auspicious blessing of the divine in an intimate, personal way.10 Packert’s photograph of Govindadeva Krishna, brethren to the Shrinathji, shows the god adorned in all his finery on a decorative stage set (fig. 7). The chapters by Orr and Packert are critical for understanding the shift in consciousness relative to the museum exhibition. As Packert notes, “Most museum visitors are attuned to appreciating works of art as unique, individually presented objects worthy of sustained contemplation. Looking and appreciating are activities generally cultivated in quiet, controlled, distraction-free settings. Nothing, however, could be further from this viewing experience than the original context that nurtured the production and reception of this image [cat.158] and many others like it in this exhibition.”11

In Hinduism, all paths are good paths to God(s).12 Simultaneity does not often seem to breed discontent, and contradictions do not lead to dead ends. There are many gods, but their multiplicity does not imply that any of them has partial authority or a limited sphere of influence. The exhibition functioned in a similar way in that there were many layers of access, from the newly initiated to those who coveted the chance to see gathered in one place the most beautiful and rare examples of blue-chip Indian art from the best collections. Some visitors may have been overwhelmed by the multisyllabic, multi-named introduction to Hindu symbolism and iconography, and there is a long history of Western ambivalence to an artistic culture of extremes and a “seeming lack of understatement.”13 Despite this complication, it seems every attempt at straightforward accessibility was made, whether in the catalogue, in the galleries, or within the technological components that live inside and outside of the exhibition space.

Cummins’s introductory curatorial essay to the catalogue, “Multiplicity and Grandeur: An Introduction to Vishnu,” offers a contextual framework into which the remainder of the catalogue information can be easily organized. Physically, the catalogue is of a manageable heft, with only a few mechanical issues. It would have been helpful, for example, to have a reprinting or highlighting of the map on page 10 before the chapters relating specifically to a geographic location. There are occasional inconsistencies in the italicization of terms between the index and the text and within the text itself. The accession number for the Annakut picchawai on page 259 is incorrectly listed as S1992.38 (it should be S1992.28), and the captions are not always consistent in attribution (sometimes using North India, sometimes Northern India, for example). A full bibliography of sources used in the notes, while not necessary, would have been a welcome addition. However, these small issues do not detract from the dynamic design and content of the catalogue. The majority of the images are reproduced in color at half-page or larger, with contextual images that add detail to the well-written descriptive text. Overall, the catalogue authors offer depth to a conceptual framework laid by the curator, presenting more profound discourse based on Puranic texts and good old-fashioned stylistic analysis.

In the galleries, text in a more casual, familiar style was composed in favor of clarity rather than complexity. Blog entries, interactive technology,14 and material sumptuousness counteracted the mind-boggling diversity of forms, styles, and mediums. Most significantly, the religious foundation of the exhibition was embraced and expanded on in a way that reminds us these artworks are prayers–as Cummins put it, “The prayer was heard by anyone who visited the temple or opened the manuscript, . . . it was heard by the gods; and in the case of the objects illustrated here, it continues to be heard today.”15

Allysa B. Peyton is curatorial associate for Asian art, Samuel P. Harn Museum of Art, Gainesville, Florida.

- 1. Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, “Why Exhibit Works of Art?,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 1, no. 2/3 (Autumn 1941): 27–41.

- 2. Manifestations of Shiva (March 29–June 7, 1981) organized by the Asia Society for the Philadelphia Museum of Art; Devi: The Great Goddess (March 28–Sept. 6, 1999) at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery; The Sensuous and the Sacred: Chola Bronzes from South India (Nov. 10, 2002–March 9, 2003) at the Freer|Sackler Galleries; Shiva Nataraja: The Cosmic Dancer (Nov. 16, 2008–March 1, 2009) at the Museum Rietberg, Zurich; Mother India: The Goddess in Indian Painting (June 29–Nov. 27, 2011) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art; The Elegant Image: Hindu, Buddhist and Jain Bronzes from the Indian Subcontinent in the Siddharth K. Bhansali Collection (Aug. 5–Oct. 23, 2011) at the New Orleans Museum of Art; Journey to India Mythology (Aug. 9–Sept. 9, 2011) at the National Folk Museum of Korea.

- 3. See Wen C. Fong, “Why Chinese Painting Is History,” Art Bulletin 85, no. 2 (June 2003): 258–80; Henri Zerner, “Editor’s Statement: The Crisis in the Discipline,” Art Journal 42, no. 4 (Winter 1982): 279.

- 4. This relates more specifically to temples and the new methodologies of display as proposed by independent scholar Deborah Stein for the 2012 College Art Association (CAA) conference in Los Angeles.

- 5. Joan Cummins, “Multiplicity and Grandeur: An Introduction to Vishnu,” in Vishnu: Hinduism’s Blue-Skinned Savior (Ahmedabad: Frist Center for the Visual Arts in association with Mapin Publishing, 2011), 11–23. The essay was also published in its entirety in the Asian Art Newspaper, April 2011.

- 6. The audio tour and a PDF version of the gallery guide are available on the museum’s website at http://fristcenter.org/calendar-exhibitions/detail/vishnu-hinduisms-blue-skinned-savior.

- 7. The Brooklyn Museum’s collection of Indian paintings ranks among the top ten in the United States, representing the artistic traditions of many different regions, with examples dating from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century. Cummins, formerly assistant curator of the Department of the Arts of Asia, Oceania, and Africa at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, wrote Indian Painting: From Cave Painting to the Colonial Period (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2006).

- 8. Further experimentation in the Brooklyn Museum resulted in the concurrent exhibition Split Second: Indian Paintings organized by the chief of technology, Shelley Bernstein, in consultation with Cummins. One of the conclusions of this interactive online experiment was that viewers’ overall rating of an artwork goes up after they are given information about it. See http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/labs/splitsecond/.

- 9. Depending on the study, the average viewing time of a single work ranges from seven seconds to two minutes. A similar technique, aimed at slowing the visitor down and increasing the number of viewings for a particular work, was employed at the Frist Center for Visual Arts. The Frist produced, with Cummins, an educational guide focusing on the ten avatars of Vishnu and their attributes. The e-mail component was available only at the Brooklyn Museum.

- 10. For a comprehensive source on the nature of Hindu imagery and darshan, see Diana L. Eck, Darśan, 3rd ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996).

- 11. Packert, “Networks of Devotion,” 45.

- 12. In her introductory essay to the catalogue, Cummins summarizes as follows: “Although the many schools of Hinduism have certainly clashed on occasion, there is a tendency within the religion to accept discrepant teachings as paths to the same goal.” Cummins, “Multiplicity and Grandeur,” 12.

- 13. Partha Mitter writes about the history of the British relationship with India, “Just when one felt confident that India was under control, it suddenly reverted to its true nature: eluding understanding, escaping into its own world of disgusting cults, weird customs and lascivious fakirs.” Mitter, “Imperial Collections: Indian Art,” in A Grand Design: The Art of the Victoria and Albert Museum (New York: Abrams, 1997), 222–29. For an extended discussion of the topic, see Partha Mitter, Much Maligned Monsters: A History of European Reactions to Indian Art (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992).

- 14. Blog entries are archived and can be subscribed to by RSS feed at http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/community/blogosphere/. Visitor comments collected online and from the galleries are posted on the Brooklyn Museum exhibition website at http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/vishnu/. The page also includes a running tally of how many visitors each avatar accompanied through the exhibition.

- 15. Cummins, “Multiplicity and Grandeur,” 23. Other noteworthy reviews of the exhibition include Lee Lawrence, “From Stillness, Cosmic Action,” Wall Street Journal, Aug. 4, 2011; Holland Carter, “Basking in the Presence of an Ever-Changing God,” New York Times, July 7, 2011; Joseph Sutton, “Vishnu Smiles upon Brooklyn Museum,” Brooklyn Exposed, July 5, 2011; “Vishnu Exhibit Brings Hindu Holy Art to US Audiences,” USA Today, March 10, 2011; “Frist-Center Organized Exhibition ‘Vishnu: Hinduism’s Blue-Skinned Savior’ First Major Museum Exhibition to Feature Deity,” AllWorldReligion.com, Feb. 2011; BWW News Desk, “Frist Center’s Vishnu: Hinduism’s Blue-Skinned Savior Opens, 2/20,” BroadwayWorld.com, Dec. 23, 2010.

Catalog cover of Vishnu: Hinduism’s Blue-Skinned Savior, featuring Vishnu Flanked by His Personified Attributes, Central India; tenth century, sandstone, 40 1/2 x 22 5/8 x 8 in. (102.9 x 57.5 x 20.3 cm). Krannert Art Museum and Kinkead Pavilion, University of Illinois, Urbana–Champaign. Gift of Elinora D. Krannert.